In this episode, we expose the shocking realities of environmental racism and its devastating impact on public health. Toxicologist Dr. Shannon Z. Jones joins us to discuss how pollution from industries and landfills disproportionately harms marginalized communities. From the notorious “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana to the clean water crisis in Flint, Michigan, learn how systemic issues create health disparities. Dr. Jones shares her powerful journey from growing up near a polluted paper mill to empowering students and communities to fight for environmental justice. This conversation is a crucial look at toxicology, community activism, and the fight for basic human rights.

In this episode we cover:

- What is Environmental Racism? A clear definition and its connection to institutional racism, health disparities, and social justice.

- Toxicology in Real Life: Dr. Jones shares her personal story of growing up with polluted water containing sulfur and heavy metals, and how it led to chronic illness in her family.

- Superfund Sites Explained: Learn how to use the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) to identify the most toxic sites in the United States and investigate pollution levels in your own community.

Shannon Jones’ Links:

Instagram: @szj7484

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/shannon.z.jones

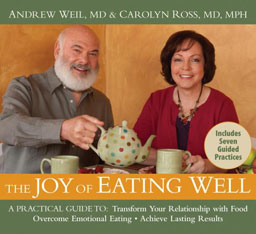

Dr Carolyn’s Links

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/carolyn-coker-ross-md-mph-ceds-c-7b81176/

TEDxPleasantGrove talk: https://youtu.be/ljdFLCc3RtM

To buy “Antiblackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies” – bit.ly/3ZuSp1T

Hi, this is Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross, bringing you the Inclusive Minds Podcast. This podcast was inspired by the book of which I’m a co-editor entitled Anti-Blackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies. Lived experiences in the fight against institutionalized racism. If you’re a psychologist, a social worker, an addiction professional, or a healthcare provider, or anyone who wants to broaden your horizons, then this podcast is for you.

The goal of the podcast is to help you understand some of the more complex issues facing our culture today. My guest. Are experts in their fields, and we’ll be talking about a wide array of topics including cross-cultural issues, the intersection of race and trauma, social justice and health inequities.

They will be sharing both their lived experiences and their expert opinions. The goal is to give you a felt experience and to let you know that you are not alone in being confused by these complex issues. We want to provide nuanced information with context that will enable you to make your own decisions about these important topics.

Carolyn Ross MD: Hi, everybody. This is Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross. Welcome to the inclusive minds. Podcast. Today we have Dr. Shannon Z. Jones, and she wrote another chapter in our book, Anti-blackness and the stories of authentic Allies lived experiences in the fight against institutionalized racism.

Dr. Shannon Z. Jones earned her Bachelor of Science in Molecular Biology from Winston-salem State University, and her Phd. In Toxicology from UC. Chapel Hill she continued her research at UNC Chapel Hill, studying air pollution’s effects on the immune system. Before joining the University of Richmond’s department in 2015, Dr. Jones teaches courses on toxicology, interdisciplinary science and environmental impacts on communities and she mentors undergraduates in research on immunotoxicity. Her interests include the influence of environment and nutrition on immune function as well as environmental justice and pollution in marginalized communities. Welcome to the show, Shannon.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Thank you. I’m excited to be here. Thank you for having me.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah, well, your chapter was amazing. I learned so much, and the title of the chapter is Environmental Racism in rural America. So can you start us out by telling us what is environmental racism?

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely. So I view environmental racism as a violation of basically of civil rights and basic human rights. And the philosophy behind environmental racism is that most often communities of color, and it’s usually impoverished or low income communities are more likely to be impacted by the burden of pollution wherever they live. And when I mean, when I speak of burden of pollution, I’m talking about industries that emit toxic chemicals into the air and the water, and study after study have shown that communities of color and low income communities are more likely to live in these areas that are heavily polluted. And it’s not by accident And it is a consequence of institutional racism.

Carolyn Ross MD: Oh, wow! And that’s despite the EPA and all of the other regulations we have in place.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely and oh, sorry!

Carolyn Ross MD: Still going on right.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely. Yes, I mean the earliest, say I would say the event that inspired the movement happened in the seventies. One of the earliest cases happened in a middle income black community in Texas, and that’s really ignited the movement. And again, that was back in the seventies. So this this concept.

Carolyn Ross MD: What? What was the pollution there?

Dr. Shannon Jones: So they. There was a community that was fighting the placement of a landfill in just within a few feet of a school in their neighborhood. And what was interesting about that case is that they were. They were a black community that weren’t impoverished right? There was middle income community, and they were going to have this landfill called from whispering pines landfill placed in their community. And so there was a call to action they actually sued. That was the 1st time a lawsuit had been filed citing racial discrimination when it comes to the environment. was sort of the key event that ignited this movement, and soon after there was another case in my home State of North Carolina.

in Warren County. They were a similar case. They were fighting the placement of a landfill that contained known cancer, causing agents being placed in Warren County. And so those 2 cases back to back really ignited a movement and a conversation about how communities of color, especially black communities, are most often targeted by these polluting industries and placement of these industries.

Carolyn Ross MD: So how did you 1st become interested in this subject? In toxicology and all of that that you’re studying now.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Sort of my career is at Stace, and what I always tell my students and people who want to listen to my story is that where I ended up is very much a part of my is because of my lived experience, and how and where and how I grew up. And so I have been personally impacted by issues of environmental injustice or in environmental racism. And I grew up in rural North Carolina, where most of the income for the county that I’m from Washington County. Still, today comes from a paper mill that operates in my county, and paper mills are notorious for spewing out very toxic chemicals into nearby bodies of water. And so my 1st experience with this was having to do with where I grew up in this rural community with limited resources and and.

Carolyn Ross MD: Said in the chapter that your family basically was living off the land.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes.

Carolyn Ross MD: The water coming from a well that you used for everything, bathing and drinking and cooking, and so on. And did you find out that that water was polluted.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely, I always knew noticed growing up. It had an awful smell, and I just thought that was how water smelled like I didn’t know any difference in it. I learned later that it was because of the way our water was being secured from this well, that it had this smell of rotten eggs, which I later learned was sulfur. And so I just remember our clothes when we washed them, would always come out like brown or yellow. So my mom had to. We like we took our clothes to a laundromat a few miles away, because we couldn’t use our water at home. So we we were careful about what we like using it to cook and and so it was just that was my normal life experience growing up. And we later found. And as I started going to school, I developed an interest in biology and like drawing connections between our environment and our health. And so it really ignited a curiosity for me, especially when several members of my family were diagnosed with these chronic illnesses that we really couldn’t explain where they were coming from. And so it’s just like all the pieces started fitting together, and that our water contains toxic materials that could be impacting our health. When many of my family members were diagnosed with chronic immune conditions that are.

Carolyn Ross MD: Autoimmune condition.

Dr. Shannon Jones: I mean yes.

Carolyn Ross MD: And so what were the pollutants that you found found in the water?

Dr. Shannon Jones: So well. Water is often contaminated with a chemical called trichloroethylene, and so it would be years later, when we actually did some testing, I was almost an adult when we actually found out what was in the water. But there are a lot of organic materials, so carbon containing, like volatile chemicals. One of them is tce. There are some metals in there which.

Carolyn Ross MD: Heavy metals.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Heavy metals were in there at low concentrations, but we know, like low concentrations, are enough to cause illness in humans. There is like.

Carolyn Ross MD: Usually over time. If you’re.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely.

Carolyn Ross MD: That water since birth.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Exactly.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: And so, you know most of my family. We try not to use the water that comes out of tap, especially for cooking. We still use it for bathing, but for cooking, we technology has advanced in some ways that we can filter it. So we do. We have filters in place now and then. In some instances we we rely on like bottle bottled or or gallon water, which also contributes to environmental issues because they’re accumulating plastic now. So it’s.

Carolyn Ross MD: I had. I had a similar situation and I didn’t even think about it as being part of this, but I used to live in Denver, and I bought a home in the Metro Denver area in a historically black community, and it was, you know, I loved my home and everything, and after we had been there for I don’t know probably 6 or 7 years, the city came in and started going house to house, giving us, you know. What do you call those Brita filter containers that were specially designed to get rid of lead because they had these old pipes in the city. And the same thing happened when I bought another house for a rental property in another black part of the town, and then they came in and started digging up the pipes. But there was lead in the water in that part of Denver not everywhere in Denver, but yeah, in that part of dinner. So you you mentioned how environmental racism impacted your own family. But in your chapter you talk about a really interesting course that you teach at the University. It’s at the University of Richmond, where you said, how is it that certain groups of people do not have access to basic natural resources are, or are systematically burdened with pollution or environmental hazards to a greater extent than other groups. So how do you have students investigate that question?

Dr. Shannon Jones: Well, I tell them, to start in their own backyard, look in their own community, and one of the 1st assignments I give them is to use a database, basically, that is run by the Environmental Protection Agency, where you can search by year, by state, by city. And what that report will give you is all of what we. What are referred to as superfund sites and superfund sites are designated as the most toxic, or these areas across the United States are highly polluted with dangerous chemicals, and they’re labeled a superfund because the danger is deemed so high that the EPA has to invest government funds for cleanup and students are.

Carolyn Ross MD: So that’s the worst of the worst.

Dr. Shannon Jones: That is the worst of the worst, and and some, unfortunately, some of them are ongoing. Some of them have been resolved, but many of these cases are ongoing actually turns out that the county that I grew up in has a superfund site. And so that’s what gave me the idea, for this assignment is because sometimes students think that these issues are far removed from them.Doubt that they’re not. And so it’s, I think it’s a very impactful experiment. Say, to look in your own communities, look in your city in your, you know. Search by your Zip code, and likely you may even find more than one.

Carolyn Ross MD: Hmm.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So I use that to engage them, ignite their interest and passion for the topic. Because I think this is how we generate change agents right.

Carolyn Ross MD: And how how many of them end up finding superfund sites near their homes.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Oh, I would say over half.

Carolyn Ross MD: Wow, a lot.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Over, half.it is. And sometimes they even have international students where there’s another database that we use is called the environmental justice atlas that looks at global cases of environmental justice. And so I’ve had students from South America, from some Asian countries. So in India. And so I give them the opportunity to also look. We expanded beyond the United States and they find cases as well. So it’s a global.

Carolyn Ross MD: How do the students respond when they discover this.

Dr. Shannon Jones: It’s interesting because it depends on their own understanding of the legacy of racism. So some of them, it’s like, of course, this happens right like they kind of expect it, and then others are shocked, especially when they ask, Well, what’s being done about it? And in some cases we can’t say it’s resolved, and so there’s some frustration of like or of the unfairness of it, that there is no resolution, I think that’s the hardest part for them to to grapple with is that these cases are ongoing, and sometimes there doesn’t seem to be a resolution for the people that have been impacted. I think that’s the hardest part is, how do we remain positive like? How do we remain having positive feelings and feeling hopeful when there’s so many of these cases that have not yet been resolved.

Carolyn Ross MD: And when you think about the superfund side near where you live, and I’m sure many of the students still have family members living in those areas. So there’s that I’m sure the worry that.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes.

Carolyn Ross MD: So what do we do? So when you found out about the superfund site near your family home, what can you do about it?

Dr. Shannon Jones: I was mostly shocked because it had happened so many years ago, and I never heard about it. None of my family members knew about it. And this this case happened about almost 50 years ago, and so it had been resolved. But just the fact that so it got resolved, maybe in the late nineties, which is when I was growing up, but the fact that it had existed for so long, and there’s also a conflict of feelings there, because the source of the pollution generated income for my family right.

Carolyn Ross MD: Is that the paper mill.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yeah, that’s the paper mill.

Carolyn Ross MD: Okay. Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So.

Carolyn Ross MD: And you said your uncle’s.What’s that smell? Your uncle said the smell of money.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Exactly, and a lot of people in the town still think to this day that they rely on this for income. And it’s just a part of life. That paper mill still exists. And so I like to think, okay, that particular issue was resolved. But the mill is still there, still emitting air pollution. So how much of it is really resolved? Right? And so they’ve tried to mitigate their release of toxicants into the water. But there’s still the air pollution there, and so I say, it’s resolved. But.

Carolyn Ross MD: But it’s not, it’s never gonna be completely resolved. So you also said that you learned a lot from the exercise that you gave your students. What did what was that like for you?

Dr. Shannon Jones: It’s so finding out about my own family’s experience, it made me want to amplify the voices of the people that have been impacted. And so by teaching this class and working with the students.it feels like my mission now is to advocate for people who have been impacted, not just people from my hometown, but people all over the Us. And in other countries. And so what I’ve learned about it is the power of our voices.

Carolyn Ross MD: Oh, wow! That’s.

Dr. Shannon Jones: And it may feel like one person can’t make a difference. But but if we continue to tell our stories collectively, we can. And I think that’s the biggest lesson that I’ve learned is not to be. I mean, it makes me sad, but it’s not enough to stop the work that I’m doing. It’s actually doing the opposite. It’s energizing me to again to tell the stories of the people who are impacted, which is the impetus for my course. We travel to different Ej communities across the Us.

Carolyn Ross MD: Oh, for example, like.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So we have gone to Cancer Alley in Louisiana. I’ve taken students to Cancer Alley in Louisiana.

Carolyn Ross MD: What’s the source of the pollution? There.

Dr. Shannon Jones: It’s all the oil refineries. So it turns out that between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is about 85 miles along the Mississippi river, where there are over 100 oil refineries and petrochemical companies, and because they’re along the river all the waste that those oil refineries release it gets into the water, and most of the people that live in that area are again mostly people of color, black families, middle to low income families, and it was a morbid nickname they received called Cancer Alley, because at 1 point in time that particular region had almost 10 times the cancer incidence in the rest of the country.

Carolyn Ross MD: Oh, yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: And so it’s 1 thing to read about it. But it’s another thing to see it firsthand. And so that’s what I wanted my students to take away from it. And that’s what I continue to take away from it is we’re not just reading about these abstract concepts. These are real people impacted by pollution.

Carolyn Ross MD: So what are some of the other sites you’ve traveled to with your students.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So the others place we’ve gone to recent. So I’ve taught this class 4 times. So the 1st 3 we went to different parts of Louisiana. And then this, most recently we traveled to Puerto Rico. Yes, and so that was last year, and the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico is of great.

Carolyn Ross MD: A whole nother story.

Dr.Shannon Jones: But I like to say that that’s 1 of the reasons why Puerto Rico has so many issues. So we talk about climate, justice, right lack of access to health care and how that can interplay with environmental pollutants there. So they have a coal ash problem. They have a landfill like trash problem. So we try to dissect all of the issues, and at the root of it is racial discrimination and the othering of people that are supposed to be us citizens, so there was so much to unpack there.

Carolyn Ross MD: So the coal ash is, is that a plant that a coal plant.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So they still rely most heavily on coal there. So it’s it’s from coal plants. Yes.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah, and what kind of health issues are showing up from that.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So. Oh, I forgot. One other issue is Vieques. So Vieques is a small island off the coast of mainland. Puerto Rico and the us had military practices there, and they left behind a lot of ammunitions and heavy metals, so they didn’t clean up their mess. The Us. Navy left a ton of ammunitions behind on that island. And so, even compared to mainland, Puerto Rico.residents of Vieques have higher incidence of cancer like a lot of breast cancer diabetes, poor maternal health outcomes. But really what we focus on was the higher incidence in cancer directly caused by heavy metals left behind from those ammunitions. When the US Navy occupied that island of Vieques.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah. And has anything been done about it? Or is it still because you said it was just you went a year ago, right?And nothing has changed. Yeah. Puerto Puerto Rico is an orphan state, basically.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Right right, and they’re not receiving the aid they should, as us citizens. So again.

Carolyn Ross MD: The hurricanes that they were meant to have, and so on. So.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Right.

Carolyn Ross MD: It’s hard to think about. Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: The difficulty students have is again grappling with these very heavy topics. And how to again remain hopeful. And and yeah, that that’s a hard thing to, and I grapple with that as an instructor like, how much of this do I show them? But this is the real world, right? These these issues exist.

Carolyn Ross MD: I think when you show them they’ll never forget it.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Right, right.

Carolyn Ross MD: You talk about it in class, it’ll be there, for, you know, maybe a week or a month, but when when you take them somewhere that is very powerful. That’s exciting to hear about. Yeah.

So in your chapter, you also talk about that. For the 1st time in Us. History, the Federal Government, led by the Biden Administration, has set a goal that promises that 40% of the overall benefits of any Federal investment will be received by communities affected by the pollution. So how’s that going.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Not great right now. I remember the day that. So I showed this website to my students last year. It’s called Justice 40 Initiative. And I said, this is the 1st time environmental justice has been featured on the White House webpage like we looked at the web page, and very soon after this new administration took over that Webpage is gone.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah, as are most other web pages having anything to do with black and brown people.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Right to me that was just very symbolic of erasure, and that these efforts, that and these commitments that have been made no longer exist. We were having for several years open dialogue about environmental justice. Michael Reagan, like the former director of EPA, appointed by Biden. Right he he visited Ej Communities. He went to Warren County, where the 1st Ej Case or environmental racism case was fought, and it felt like we were taking a turn for the better. And now I just seems like all that work has been erased. Unfortunately, so the justice 40 initiative, to my knowledge, is gone.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah. Yeah. Now, there was the movie, Erin Brockovich.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes.

Carolyn Ross MD: Was that? What year approximately did that happen? And is that another example of environmental racism and maybe not racism, but having to do with communities living in poverty. Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, and I can’t remember the year. But I do talk about this case with my class. It happened in Hinkley, California. So not exactly a case of environmental racism, but definitely environmental injustice where the community that was impacted the low and middle income community. And it was by the Pg and E electric Company. And so it was very, it was told, very well in the in the movie. But I’ve since then done some research on the case. And again, I can’t recall the exact year. But there’s a very well known case of environmental injustice, and the fact that there was just inaction to fix it right. It took.

Carolyn Ross MD: Are there? Are there any current or recent environmental injustice cases that have been in the news.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Of course there’s Flint, Michigan.

Carolyn Ross MD: Oh, yes. Okay.

Dr. Shannon Jones: That one’s. It’s it’s it’s so hard to believe now that’s been over 10 years ago. But.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: I believe. So. There’s Flint, Michigan. There’s there was a water crisis in Jackson, Mississippi, still ongoing. They’re always lead problems. Unfortunately, you find these cases in like heavily populated urban areas. So Washington, DC. Has had a lead crisis where I live. Currently, Richmond, Virginia, has had a lead crisis cities in New York. So until all those lead pipes get replaced.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Fortunately these cases are going to make the news and and so I always tell students that.I’ll I’ll be teaching this class as long as I can, because this issue is going to exist. you know, for likely the rest of my lifetime, and I’m not going to stop.

Carolyn Ross MD: Okay.

Dr. Shannon Jones: These stories, my story, other people’s stories.

Carolyn Ross MD: Do you have any worries for yourself and your own health?

Dr. Shannon Jones: I do. I mean, and and the environmental impact on our health is a complicated topic. Right? It’s not just our environment. It’s also our genetics. Right? So I think about my family history of diseases. And so it is a combination. I know.

Carolyn Ross MD: Also in, you know, intergenerational.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, exactly.

Carolyn Ross MD: Changes that have been may be fostered by these toxins.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Absolutely.

Carolyn Ross MD: You know the change in expression of DNA, it can then be passed on to you and to your children.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So I do have concerns, especially as a toxicologist. Right? I know.

These chemicals are, and it’s a little ironic, you know, going to the doctor to check on my head, knowing that I’ve had these exposures, and so I try to mitigate that as best as possible. So I try to live a healthy lifestyle. But there’s always in the back of my mind about what about these early life exposures that I’ve had, and that my family had. And so it is. A part of my is what I think about regularly, I would say.

Carolyn Ross MD: Is, are there measures that one can take? I mean, I know, in Scandinavian countries that they believe heavily in Saunas, for example, as a way to detox. Are there any studies that show how you can get rid of these toxins, or even how you can measure whether they’ve affected you.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, so there is a such thing as a biomarker. This field is becoming more, I guess. Well studied is, what are the traces left behind after we’re exposed to these toxic chemicals. What are some things in our blood that we can measure to see if we’ve been exposed? And it turns out, almost everybody, and it’s hard to avoid exposures. But what also I saw I conduct research with students, and I’m interested in nutrition, and how our diet impacts how we respond to these chemicals. And it turns out so there’s not necessarily like a detoxification pathway. But our diet does pay a play. A big role in our immune health. So it turns out, there are lots of plant products that have these natural antioxidant properties.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Can block the effects of.

Carolyn Ross MD: And then our natural detoxifiers, like cruciferous.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, exactly. So. That’s what I study. I study the effects of air pollution on the immune system, and we look for products that have natural anti-inflammatory, antioxidant properties, and those include cruciferous vegetables.

Carolyn Ross MD: Like broccoli and cabbage, and.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, yes, so I’m I’m a big fan of of promoting nutrition, and that was one of the things that came out of the flint crisis is where it found. They found that flint is a food desert. And so the kids that were impacted were even more severely impacted because they were had malnutrition right.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So the doctors actually were prescribing fresh fruits and vegetables to help block the effects of the lead. So our health, like all these issues intersect right? So not only do they have a lead problem, they have an access problem to fresh fruit and vegetables, so that to me is a perfect example of how multiple factors intersect it to impact our quality of life. And so.

Carolyn Ross MD: And our longevity too.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Exactly, exactly.

Carolyn Ross MD: So if it if someone is listening and they want to check for themselves, where can they go to find out if there’s a Super Fund site near them.

Dr. Shannon Jones: So as long as it exists, the EPA website is a good place to start as long as we have the EPA. I don’t know how much scrubbing has happened, but that’s that’s a good place. That’s how I actually found out.

Carolyn Ross MD: The environmental protection aid.The site and on their site, they’ll say.

Dr. Shannon Jones: There’s yes, you can search your Zip code or your city and you. It’ll give you the most recent. I recently identified.

Carolyn Ross MD: That’s probably worth doing. I don’t know that many of us could move if we are a site, but maybe we could eat more broccoli that’s for sure or exercise, or get a small sauna in our backyard. Whatever.

Dr. Shannon Jones: And I would say, the Local Health Department also has information about exposure when it comes to like let heavy metal exposures. That’s another place to start. But the the website for the EPA is called the Toxic Release inventory.

Carolyn Ross MD: Toxic release inventory. Okay? And what if they find? Yeah, there is a superfund site near me. What can I do? You know, if I can’t move. What can I do? What are some options that you tell people.

Dr. Shannon Jones: I would say, mobilize. That’s the 1st thing that people can do to know that they’re not alone. Right? So you know, town meetings, a place for folks to gather, to come together to see what that they’re all impacted. And the best thing to do is go to your local officials, city officials, government officials to make.

Carolyn Ross MD: You mean your elected officials.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Yes, yes, elected officials is the best place to start and to voice your concerns because you could also request it’s called a freedom of Information act right that you have the right to request this information about what exposures you’ve had, and so even local EPA offices they are required to give that information to us. If it’s requested right? So I would say, mobilize you know, these grassroots efforts can have an amazing impact. And I’ve seen that firsthand in.

Carolyn Ross MD: Have you, have you seen any of your students using AI resources in in order to either learn more about this or or create activism around this.

Dr. Shannon Jones: I encourage them to. A lot of people in higher education are a little afraid of AI right now, and but I tell them to use it as a tool, right? Like, just like we use any other website like you can. And there’s a particular site called Ej. Atlas, and the Ej stands for environmental justice, Atlas and It gives you a global scope of environmental justice issues. And so one of the final assignments I have, my students do is to make a public service announcement about a particular case. So again, it’s amplifying people’s voices. So they can create a podcast they can create a social media presence. They can create a video. And so a lot of times, they do take advantage of AI tools to generate these projects which turn out amazing.

Carolyn Ross MD: I have to say. Your course sounds incredible. I want to take it.

Dr. Shannon Jones: The things I’m most proud of. I’ve done lately. It makes me feel like I’m using science for good, right? Like.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Jones: And to create new change agents right for the future. So it’s 1 of the things I’m most proud of.

Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah, and we have to keep fighting the good fight. So I like to ask my guests, do you have hope for the future? Given all that we’re dealing with right now.

Dr. Shannon Jones: I do, because if we don’t have hope, what else is there? Unlike what? And I? I have hope that my my students are active. I I can’t. They think about things in a way that I wasn’t thinking about when I was 20-19 27. they give me hope they’re like they get out, and they act right like they’re not afraid to to raise their voice. So they give me hope. They’re energetic. They care about these topics. They care about each other, they care about the world. So that’s that’s where my hope is coming from. Awesome.Carolyn Ross MD: Yeah, wonderful. Well, it’s been great to talk to you, Dr. Shannon Z. Jones, and we look forward to hearing more from you and your students.

Dr. Shannon Jones: Thank you so much. This is amazing. Thank you for this opportunity to share a little bit of my story.

Carolyn Ross MD: Very welcome.