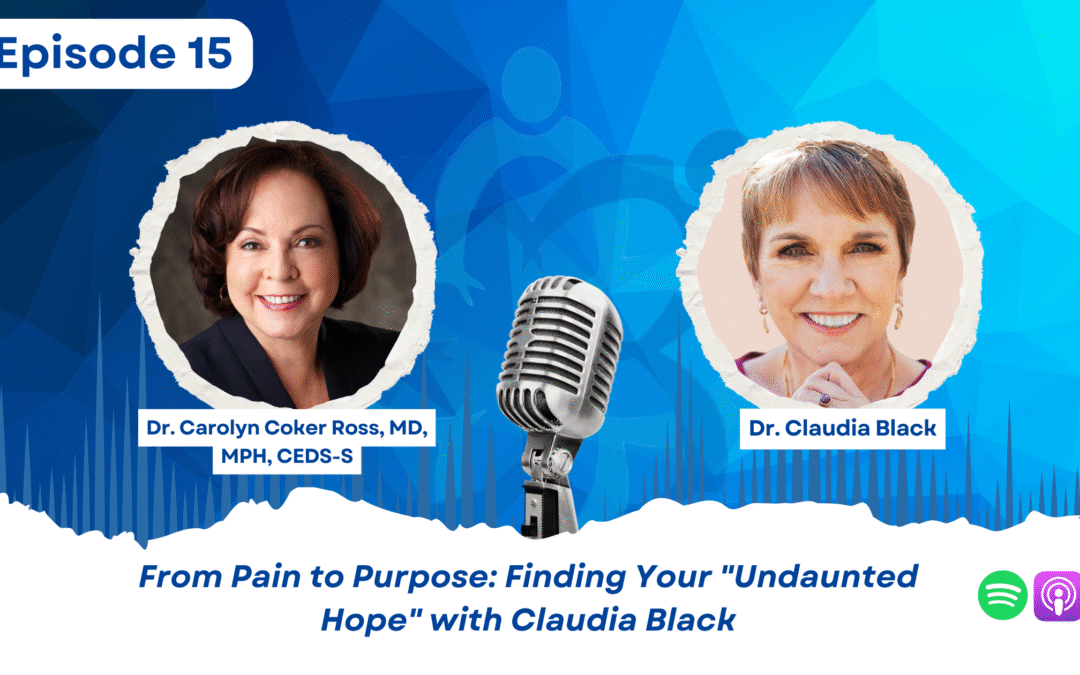

In this powerful episode, Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross speaks with pioneer in addiction and trauma recovery, Dr. Claudia Black. The discussion centers on the deep, interconnected issues of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), toxic shame, and the urgent need for a complex approach to healing addiction and mental illness. They explore how early life trauma fuels destructive adult behaviors, the necessity of treating trauma alongside addiction, and the escalating crisis facing youth due to the pervasive negative impacts of social media and overprotective parenting. Dr. Black shares insights from her latest book, Undaunted Hope, offering a roadmap for true transformation.

Guest Links:

https://www.facebook.com/ClaudiaBlackPhD

Dr Carolyn’s Links

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/carolyn-coker-ross-md-mph-ceds-c-7b81176/

TEDxPleasantGrove talk: https://youtu.be/ljdFLCc3RtM

To buy “Antiblackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies” – bit.ly/3ZuSp1T

Hi, this is Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross, bringing you the Inclusive Minds Podcast. This podcast was inspired by the book of which I’m a co-editor entitled Anti-Blackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies. Lived experiences in the fight against institutionalized racism. If you’re a psychologist, a social worker, an addiction professional, or a healthcare provider, or anyone who wants to broaden your horizons, then this podcast is for you.

The goal of the podcast is to help you understand some of the more complex issues facing our culture today. My guest. Are experts in their fields, and we’ll be talking about a wide array of topics including cross-cultural issues, the intersection of race and trauma, social justice and health inequities.

They will be sharing both their lived experiences and their expert opinions. The goal is to give you a felt experience and to let you know that you are not alone in being confused by these complex. Issues. We want to provide nuanced information with context that will enable you to make your own decisions about these important topics.

Hi everyone and welcome to Inclusive Minds podcast. I’m Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross. And as you know, this podcast is inspired by the book that I’m the co-editor of, which is Anti-Blackness and the stories of authentic Allies Lived experiences in the fight against institutionalized racism. I have a very special guest today.

Claudia Black, who is uh, a renowned author, speaker, and trainer, internationally recognized for her pioneering and contemporary work with family systems and addictive disorders. Her writings and teachings have become a standard in the fields of addiction and trauma. She is a founder and serves on the advisory board of the National Association.

For Children of Addiction and the Advisory Council for the Eluna Foundation and its development of Camp Mariposa, a camp for children of addiction. Claudia is the clinical architect of the Claudia Black Young Adult Center and senior fellow at the Meadows in Arizona. She’s the author of over 17 books.

Most notably, it’ll never happen to me. And her latest titles being Undaunted Hope, which we’ll be talking about today, and your recovery, your life for teens. Welcome to the show, Claudia. Thank you. My pleasure to be here. We tried to do this not too long ago. My internet went out. Yeah, I know. This is the third time we’ve tried to podcast together.

The first time was, I think, uh, probably 2017. It was a long, long time ago. Time ago. Yeah. Yeah. Well, show us your book so everybody can get a picture. I’m now, this is Undaunted Hope. And, uh, undaunted Hope is actually, I utilize stories of people who’ve been through a treatment process coming in for a variety of different addiction issues, mental health issues, and the underlying issue do so much of that is trauma.

And so while I utilize people’s narratives in many cases, then I also do commentary for the reader to be able to maybe better understand certain. Concept. And then I also, uh, utilized a lot of the other senior fellows at the Meadows to make commentary such as Dick Schwartz, Peter Levine, ion d Dayton. So there’s a lot of good educational material in there for the reader, not just the inspiration.

And I thought that was what was so unique about the book. I. Of course, I love the narrative stories, right? Because that really gives you a feel for what people are going through. But then to have other experts besides yourself come in and talk specifically about each case. I thought that was really genius, actually.

Yes, I love that. Thank you. Yeah, it was, it was fun and I, you know, I wanted to, what I really wanted to do was. I wanted people to better understand that there’s not always just a answer, one sum answer to the A complex problem. There’s not just one solution to treating and recovering from depression or to recovering from a substance use addiction.

And. So I wanted them to see the complexity of it, but I wanted them to also see the possibility of hope, and that if these people can find a path to healing, given the complexity of their lives, wherever somebody is on the continuum and people don’t have to get to a point that they have to have inpatient treatment.

As I say, wherever they’re at, if they can reach out for help, that help is available. And there’s a variety of different ways of which to approach that healing. Yeah, so there was a fun book to do. You definitely accomplished that. And the stories were amazing. I mean, you and I, I think we. Been in the field for, for approximately the same length of time.

Decades, in other words. Yes, yes. Multiple decades. Yes. And, um, you know, and I’ve seen these kinds of complex cases as well, and, and just, I mean, I think it’s, it’s very revealing to show how someone goes from something happened to them as a child and then. All, all throughout their lives, they are plagued with one thing after another, whether it be depression or substance use disorders, or, you know, other, other problems that they’ve had, including medical problems that can happen as a result of adverse childhood experiences.

So I, I think it’s just a wonderful book. It’s easy to read. I, I really enjoyed it. So, but you’ve written. Even more books than I have. You are one of the few that I know who’s talked to me in the book writing contest, but you have, and I just wonder why this book now, I was asked. If I could talk about the kinds of complex issues that we work with at The Meadows and I really wasn’t sure how to go about that.

And I always use stories when I speak. I use stories when I’ve written, I use stories and that’s just sort of almost expected with me, but I didn’t, you can find, you can get a book where somebody’s telling their memoir and you know, somebody tells their narrative, tells their story, and you know, as to why now.

I think that in many ways people minimize the seriousness. You know, everybody’s depressed, everybody has a substance use disorder, you know, it’s so, um, generalized today. Um, all kinds of media formats. Mm-hmm. And it’s made light of. And I do want people to understand that, that how serious this is. I mean, today.

When we see people coming in with mental health issues and addiction issues, they’re coming in with great despair. They’re coming in with very little hope and a lot of ’em are coming in extremely suicidal, and I really. Felt passionate at this point about you’ve got to give them some hope and you’ve got to give them, uh, a way to better understand what’s happening to them in a language that makes sense.

Because there’s academic books, there’s books for therapists about all these different issues, but there really isn’t, there aren’t books for the layperson. Right. And uh, I agree. And so that’s I, and the other forte I think I have is I speak to the lay person now. I do a lot of training with the professionals, but I really try and use the language that speaks to who this client could be.

And I really try and sort of put myself. And their shoes put myself in their heart at the moment. And, uh, and that’s what I really like to speak to. And yeah, I think, I think you’re right though, that, that, you know, these words have been thrown around a lot. You so and so’s depressed or et cetera, but we don’t really understand most.

Lay people don’t understand the depth at which their dysfunction, their distress really impacts their lives. And I think your book really di demonstrates that pretty clearly. Now the thing is that people really need to understand how important adverse childhood experiences are to what it is that’s happening today.

And while you know, I’ve been trying to raise that flag for a long time, or beat that flag for a long time, it’s still needs to be said. Um, yeah. Yeah, I lived in San Diego when the Adverse Childhood Experiences study came out, um, and when it was published by, uh, Kaiser Permanente, Dr. Ti and his group. And yes, I’ve been speaking about it for the past 25 years, and I’m so happy now that it seems that people, you know, when I used to say, how many of you have heard about the A study?

It’ll be like one or two little hands, and now it seems like. At least people are becoming more aware. So you, you took the words right outta my mouth. I was gonna say in the beginning of Undaunted, hope you focus on the impact of adverse childhood experiences on long-term problems. What, what were you gonna say about the impact of adverse childhood experiences on what’s going on today?

I think that today as I work with people, and one of the things I’ve always found important is to ask them what their growing up peers were like for them because there’s typically a connection, uh, that’s underlying their anxiety or, or their depression, their process addiction, their substance addiction, whatever that is.

And at some point that’s gonna be critical in terms of addressing that. Now, what I do want people to understand is. One, a person can have some form of trauma that could be underlying to their addiction, and if they treat just the trauma. Without treating the addiction as a primary disorder, they’re not gonna have the recovery process.

Right. But if they don’t treat the trauma along with the primary diagnosis, then they may sabotage having any recovery, and it certainly will set them up for a relapse. So I think that that’s a. A significant factor in needing to address this trauma. Many times it’s, what’s the barrier that keeps people from treatment as well is their trauma.

That they’re in a fight response, they know how to be oppositional, um, or they’re very good at fleeing or they’re just absolutely frozen and immobilize, so they can’t even get the help that they need. And I think that, you know, today. We’re taking that language right into, you know, the lay person’s experience for them to recognize that that’s what’s happening for them and to be willing to move beyond that enough to get help.

I think that today we work a lot to create a physiologically safe experience for them to feel sort of a sense of inner calmness, enough to be able to be present with whatever the immediate. Day-to-day problems are in their life as many people are afraid of looking at their trauma. Yeah. Yeah. And I think, I think what people need to understand is looking at your trauma doesn’t mean that you’re saying, uh, people that you love are bad people.

I think that looking at your trauma doesn’t mean that you have to rant and rave and scream and shout or end up on the floor, you know, curled up in a ball of tears, that there are ways to work with trauma that will feel safe to you, where you still feel you have some sense of control or mastery around.

What’s happening to you? We have so many more trauma modalities to help people with nowadays that Yes. You know, maybe 40 years ago weren’t present like emdr r Sematic experiencing. And you talk about some of those in the book. Yes. Expressive arts, um, role playing art therapy. Um, a big fan of EMDR. Um. And sensory motor psychotherapy, all of those kinds of techniques.

Some internal family systems is another more cognitive way of looking at our trauma. So I think that we have found some modalities that we didn’t have 40 years ago. Yeah. And certainly 25 years ago when we began this trauma work. But I think the big issue has to do with loyalty. You know, um, I don’t wanna blame other people.

I don’t wanna say, you know, it was my parents that did something and they were bad people. Um, and we’re not saying that, we’re saying things happen to you. And that response as to what it is that happened to you is triggering a lot of the maladaptive behavior today. Yeah. And I don’t know if you know, but I, I talk a lot about intergenerational trauma.

So when you talk about, you know, blaming the parents, most of the time the parents have had childhood trauma themselves. Yes. It, it can go back generations and so everybody. You had a parent who maybe was abusive or doesn’t mean you, it was right, but it may mean that, you know, that they themselves were struggling with issues.

So, and more likely than not they were, I mean, far more likely than not that they were. It’s almost always intergenerational, even from one generation to the other. And you know, people, you know, they wanna protect their parent. And again, as I said, you’re not saying your parent is a bad parent. You may say there was some bad parenting.

Um, but that doesn’t mean that the person’s a bad person, right? But there was bad parenting, there was hurtful parenting, there was not good enough parenting. And it’s a consequence of that. Oftentimes we develop core beliefs about ourselves that set us up for self-defeating behavior. I think that back to one of the first questions you asked about, you know, why this book now, the depth of shame that I see in clients, and what I mean by that is.

The inability to truly cherish themselves, the inability to know their own value is so pervasive amongst people, and that can often comes from years of, in essence, not good enough. Parenting. Uh, it doesn’t have to be abusive parenting, but certainly can come, it certainly does come from abusive parenting.

It can, it can also be overprotective parenting, what, what we call drone parents, you know? Yes. Where the child is not allowed to experience anything so that then when they grow up, you know, they have a, a crisis or a challenge and they’re just. They don’t have any skills to, and that’s very significant. In the last 20 years, we’ve seen a real shift in our culture.

You know, people talk about parents seeing the world so much more dangerous than it was when they grew up. And part of that is, is because we see. Things on television on the screen that are dangerous. But when you look really at the numbers, it’s actually far less dangerous culture today, physically dangerous than it was even 20 years ago.

But again, very overprotective in terms of our mothering, in terms of even our fathering. And as you say, it doesn’t allow the kids the opportunity to learn problem solving. It doesn’t allow the kids the opportunity to learn negotiation. It doesn’t allow the kids the opportunity to learn. Consequences. How to get up after they fall and how to get up after they fall.

That’s right. Yeah. That’s right. Yeah. And that, you know, we can learn from mistakes if our kids are never allowed to make mistakes, they don’t learn, realize they can learn from mistakes. Mm-hmm. Um, and the consequence to so much of this is kids end up with core beliefs that, um, I’m not capable. Right.

Something really bad’s gonna happen. Um, if such and such doesn’t happen, or I’m afraid to make mistake mistakes. Yes. So I’m paralyzed. I can’t do anything. Yes, yes. With that fear. So, um, you were, have worked a lot with young people. What do you think has been the impact of social media on the conditions that you’re seeing nowadays?

People so often say, well, there’s always some benefits to social media. I have to tell you, for the young people, I think the harm far outweighs the benefits. Yeah. Um, I think just far outweighs, um, you know, there’s such a quickly addictive quality to social media and I, I don’t know if people are familiar with the work of John Height.

Um, you probably are, um, when he talks about the anxious generation. But I mean, the data is certainly there in terms of. The amount of time that kids are spending on social media has, um, impaired their ability for just normal socialization. Um, yes. They dunno how to engage in free time with other kids.

They can’t, they’re not making eye contact with people. They’re looking down at the ground. Socially, you know, they’re setting them back developmentally, you know, at least a whole stage. And I think this is set up for immediate gratification. It’s a set up for, uh, feelings of inadequacy. ’cause you’re comparing yourself to everybody else and you think everybody else is having a good time and they have more friends than you, they center than you.

And for my eating disorder. They’re thinner, they’re absolutely, body images are huge. And today we have more body image issues with men than we’ve ever had before. Yeah. And I think that’s a direct result of social media. Mm-hmm. I think that women have historically struggled for years around the issue of food and body image and social media has gravely exacerbated that.

Very much so. But I think the fact that we’re seeing so much more with men has a lot to do with social media and um, you know, I think that. One of the problems is, is today the parents themselves are digital natives. I mean, we have parents that have grown up with the digital world, and so we see parents not involved with their kids because of their overuse of screens.

Yeah, you see it all the time. You go to a local park and you know, the mom sends the kids out to play on the swings, and she’s over here, you know, you know, scrolling through her social media and that you see the kids looking for the parent for some kind of affirmation, for some kind of engagement or some kind of eye contact.

Yes, yes, yes. I know. I’ve been in Starbucks and I’ve seen a toddler seated in a stroller and with their little Starbucks, and then the mom on the table, you know, looking down at her screen. And, and no interaction. It’s just like, wow. It’s, it’s amazing that that’s happening, you know? Yeah. No, it’s, it’s very, very sad and I’m thrilled.

Um, just this school year alone, the numbers of school districts in our country who are either. Setting a rigid limit that kids cannot even bring their cell phones to school. Yeah. Um, or they check them in at when they first get their first thing in the morning and they don’t get them until they leave. I think that’s important.

I think it’s also very disruptive to let them have it during the breaks. I think it’s disruptive to let them have it in the lunch hour when the whole point isn’t just for them to be attentive in the classroom. Mm-hmm. Um, but it’s also for them to have the social interaction. Absolutely. Yeah. Now in your book you say, and you just mentioned this, uh, a moment ago, but I’d like to get more into it.

You, in the book I’m gonna quote, you said, current research correlates rising depression and increased use of social media. Young people are particularly vulnerable to internalizing. Toxic media messages causing them to have thoughts like, I’m not good enough. I don’t have enough, and, and that’s what we’re all seeing I think, in our work.

So how do you advise young people or particularly young parents to break that. Habit because it’s so deeply ingrained now in our society. One of the things that I feel is really important is that parents, their job is to be the best parent, not their child’s best friend. Right? And what that means is they need to learn how to set limits and know that we’re doing this to out of love for our child to support our child and their healthy development.

Um, not because we’re trying to control issues and. That I think that it really begins very young for a young parent. You don’t give your kids screens. I think that, uh, they don’t get cell phones until they’re probably almost, uh, and I don’t even think they have to be, uh. They can be flip phones. I don’t think they get phones until they’re in junior high school and then they don’t get the phone with access to all of the internet until they’re in high school.

Um, I think it begins with setting limits about how quickly they get screens and how much time they have on screens, and are the parents able to monitor what it is that they have access to on those screens. And then it also means the parents don’t spending all that time. On screens as well. When I say on screens, it’s not just social media.

A lot of their time is YouTube. A lot of their time is on emails. A lot of their time is on Spotify. Spotify, it’s also gaming. We get a lot of gaming that’s going on. Um, so I’m talking about screen use as well overall, and not just social media, but the key, what I see is the parents. The parents use the screen though as babysitters.

Yeah. Yeah. Now I was a kid. The television was our babysitter. Yeah. And, um, I watched a lot of television. Both my parents were out of the house and sort of, we had three kids all close in age, babysitting each other. And, uh, we weren’t. They were pretty strict about not leaving the house. So we were sat in front of a television and, um, so, but today is the screen.

Mm-hmm. And I understand that, you know, parents need to get other things done and is if your kid is captivated in a screen, you know, they’re right there and, you know, they’re not really getting into trouble. But what they really need to hear is the long-term consequences of that. They, um, need to find other ways for their children to be preoccupied.

Um, without it being the screen, because the long term consequences are way too grave. One of the things is bringing children into the adult world. Like if you have to wash tissues, why isn’t your child standing there washing dishes with you, cooking with you? I had, uh, one of the people, I, uh, worked with a young woman, and she’s a single mom, and I’ve been a single mom multiple times, so I, I had a lot of sympathy for her, but she was saying.

Well, I just never get any me time. I never get to have any fun is what she said. And I just thought back and I said to her, you know, what about having fun with your kid? It doesn’t have to be all about like, okay, I have to take care of this person and that’s my obligation. What about having fun with your children?

And it had, interestingly, it had never occurred to her. She could, you know, not just take the kids to the park. She doesn’t have to go down the slide, but you know, you are at home, sit and talk. Yeah. Read a book, whatever, whatever we used to do before social media, you can put your kids right next to you and give them a book.

Yeah. Crays, you know, have them build a Lego, um, but then they’re somewhat physically close to you and they’re not just on the screen. Exactly. Yeah. So in your book, I was particularly moved by one of the clients that you talked about who had trauma, depression, and substance use disorder, and this is the one where you talked about toxic shame and you said in the book, the primary consequence of living with abandonment is toxic shame.

The painful feeling associated with the belief that who we are is not good enough, not okay that we are inadequate, not worthy or not of value in time. Toxic shame is not so much a feeling as it is belief that becomes an emotional block. Do you think toxic shame also feeds and abandonment feeds into the kind of the high level of narcissism we’re seeing in our society?

You know, the narcissistic wounding. Absolutely. I mean, I think there’s a direct relationship and I think that people’s ability in which to attach usually has to do with, uh, that parental unavailability, um, or unavailability in unhealthy ways. And I think that. Message is one that culminates in believing that somehow there’s something different about me that’s not okay and I need, and in order to fight that.

And I think a lot of narcissism is fighting that belief, you know? Yeah. I’m all powerful, I’m all wonderful. Um, I have all of the answers, and the truth is. I’m all powerful. I’m all wonderful. I have all the answers, and you’re not gonna get close enough to me to see into that, which is not okay. Exactly.

It’s a wonderful barrier. You’re not gonna get close enough to see into the, my shame, you’re not gonna get close enough to see into what I think is my damage. You’re not me. Yes. To see that which is ugly, I, they’re talking about an internal kind of ugliness and it gets really. That the behavior of me knowing how to distance people becomes a skill in the beginning is a defense needing to distance myself from people in time.

I have to practice it day in, day out. It becomes a skill and it’s just a natural way of being. Right. Yeah. I think the other thing that promotes toxic shame is the ID degree of bullying that we see with kids just, um, a week or two ago in Coronado, you know, which is a military town. It’s a beach town. It’s kind of an idyllic part of San Diego actually.

And, uh, a 13-year-old child committed suicide after being bullied for. A long period of time and no one did anything about it. They kind of blamed him because he was apparently a little different or there was something unusual about him or whatever. I think bullying is really significant. I mean, it’s very pervasive.

It is more pervasive today as a consequence of the internet. It’s been with us for generations. Yeah. And typically bullying has taken place in school settings, in the hallways, in the bathrooms, in the parking lots. Mm-hmm. But when you leave the school, it’s over. And not that the effect is over, but the bullying is over.

Today, not only is the effect not over, but the bullying continues because by the time you go home, chances are somebody has put a video. Um, of you being taunted and you get people not just within your neighborhood that are not bullying you on the internet. You can get people all across the world doing that.

And that bullying has, the suicide rate is probably two to 9%, two to nine times higher for kids who have been bullied than for other kids. And when I work with a lot of young adults today, I oversee a young adult program, kids who are 18 to 26 years of age. Bullying is one of the five predominant traumas that we see.

In fact, we even do a questionnaire. Um, one is some of these kids themselves have been the bullyer, but more often than not, and we’re seeing that our girls are bullied and our boys are bullied, and most of the time parents do not know, or they certainly do not know the extent of that bullying. I was reading somewhere just the other day that I believe is in one of the, um, countries up in the Netherland area in, in, in Europe, where actually they are taking grade school kids and they’re incorporating classes on empathy.

Did you see that for other kids? And I think that we’re probably unfortunately at a stage that we need to integrate that into our educational process because it is so pervasive. And how old was this young person in San Diego? 13. 13? Yeah. I mean, just, yeah. And it’s usually beginning this. Beginning with kids in second, third, and fourth grade.

And it does happen to kids who are marginalized. There’s something about them that people perceive to be different, and in their mind, in their differentness, they’re not okay. Mm-hmm. And that could be, they could, uh, be, uh, you know, underweight, they could be overweight. I don’t like your clothes. Your clothes aren’t cool, your glasses, you know.

Uh, you know, aren’t stylish. Um, certainly kids who are in the lgbtq plus community are more prone for bullying. Uh, kids with autism are more prone for bullying to be bullied. That’s what I’m speaking about here. But bullying is, uh, needs to be taken very, very seriously because the possibility of suicide is so much greater as I just said.

Yeah, and I think it’s important for parents to have permission to take care of the problem themselves because it doesn’t seem like at this point the school system is really prepared to handle it. They, they’re, you know. Often prepared to please the teachers or not, not, um, not please the teachers, please the parents not upset the parents of the bully or whatever it is.

But I think parents are often reluctant to, well, let’s just take our kid out of that school or find a different school for them. And I think they need to recognize that the risk is catastrophic. You know, that you can really lose your, your child. Parents need to be directly involved. I think that parents need to reach out to other parents.

I think the parents do need to expect and ask the school to be involved. I don’t think that we wanna give up on the role the schools can play. Go ahead. Yeah. In this case, they did try to talk to the school, uh, more than once, if I am not mistaken. And, you know, they, they basically kind of put the onus on the child and, well, he did this, but he did that because either he has, you know, he, it.

It wasn’t any intentional harm that he caused. He did some things that probably shouldn’t have and the parents admitted, but it, you know, anyway, I just think we need to take this a lot more seriously. I’m glad you brought it down because I see it as, as I said, one of the top five forms of trauma. And the young people that I work with and, and that’s what’s leading to a lot of their depression.

At least it fuels a lot of their anxiety. Well, I could talk to you all day, so, well, we can’t do that. I’m sure you have a life and No, I just, and I wanna say, you know, your work has been so important and I wanna thank you for all of your contributions that you’re continuing to make. Thank you and Dito, I’ve always admired you and all the things that you do, so I’m so happy we finally got to do this little podcast.

I’m gonna leave you with one question and what gives you hope? Oh, I have to say, working with people gives me hope and it always has. I feel. I mean, we’ve both been doing this a long time and I still feel extremely passionate about it. Yeah. And, and what gives me that hope is I get to be witness to what I think of as the miracles, healing, and recovery.

And they don’t happen because of fairy dust landing on somebody. Um, but it’s because we create a safe space, be it in your office, my treatment center, you know, in our environment. Um. For, for people to do what they need to do in their healing. And you know, far more people die of the disease of addiction than get well, I know that far more people probably still stay out there and struggle with depression than get well.

Um, but I really focus on the. The cup being half full versus half empty. To be able to witness the people who are willing to get through their shame and to ask for help is what really keeps me doing this work and allows me to feel hopeful. Um, as I said, it’s just. To see people who come from such complex histories, and most of us do as, uh, we’re not unusual.

Most of us do, and yet are able to transform our lives. We don’t just stop a certain behavior, we transform our whole lives. Mm-hmm. That’s what gives me hope. I love it. Yeah, me too. Well, thanks again for being on Inclusive Minds, and it was Al as always a pleasure to talk to you. Thanks for listening.

Please subscribe to the Inclusive Minds Podcast so we can let you know when the next great guest comes on. The link to subscribe is in the caption below.