In this powerful episode of the Inclusive Minds Podcast, Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross speaks with liberation psychotherapist Liana Maneese about her personal and professional journey. Liana, a transracially adopted Afro-Brazilian and Black American woman, shares her “origin story” and the deeply personal impact of anti-Blackness within her own family and most intimate relationships.

The conversation explores how racism doesn’t disappear in the presence of love and family. It instead manifests as an “unseen hurt,” with microaggressions, unexamined biases, and a defensive lack of awareness from those we are closest to. Liana introduces the concept of undoing, a lifelong process of decolonizing our minds and rejecting the white supremacist ideas that are so deeply ingrained in society—and ourselves.

She emphasizes that true healing requires more than just calling out racism in public; it demands we confront it in private, and a liberation-focused therapy offers the tools to do this. Liana’s lived experience highlights the critical responsibility of therapists to create a space where these difficult, painful truths can finally be seen, heard, and healed.

Guest Bio: Liana Maneese is a liberation psychotherapist and identity navigation specialist. She is the founder of Transitional Characters, a Pittsburgh-based liberation-focused practice, and is a member of the #NotWhite Collective. Her chapter in the book Anti-Blackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies is titled “Interracial Relationships: How Anti-Blackness Informs Kinship and Therapist Responsibility.”

Guest Links:

@transitionalcharacters (instagram)

Dr Carolyn’s Links

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/carolyn-coker-ross-md-mph-ceds-c-7b81176/

TEDxPleasantGrove talk: https://youtu.be/ljdFLCc3RtM

To buy “Antiblackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies” – bit.ly/3ZuSp1T

Hi, this is Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross, bringing you the Inclusive Minds Podcast. This podcast was inspired by the book of which I’m a co-editor entitled Anti-Blackness and the Stories of Authentic Allies. Lived experiences in the fight against institutionalized racism. If you’re a psychologist, a social worker, an addiction professional, or a healthcare provider, or anyone who wants to broaden your horizons, then this podcast is for you.

The goal of the podcast is to help you understand some of the more complex issues facing our culture today. My guest. Are experts in their fields, and we’ll be talking about a wide array of topics including cross-cultural issues, the intersection of race and trauma, social justice and health inequities.

They will be sharing both their lived experiences and their expert opinions. The goal is to give you a felt experience and to let you know that you are not alone in being confused by these complex issues. We want to provide nuanced information with context that will enable you to make your own decisions about these important topics.

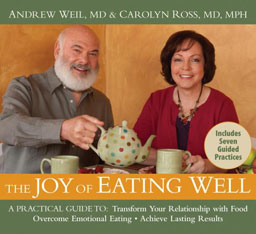

Hi everybody, it’s Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross again, and welcome to the Inclusive Minds Podcast Today my special guest is Liana Manness, and you are gonna find this talk very fascinating. So I hope you stay tuned. I wanna remind everybody that the podcast is based on our book, which Liana has a chapter in. And the book is called Anti-Blackness in the stories of authentic allies lived experiences and the fight against institutionalized racism.

So I think what makes this book special and what makes these podcasts special is, uh, people, people like Leanna talking about her. Lived experience. So it’s not a book that’s, you know, just for people to read in college or you know, people to get facts from. It really focuses on lived experience. So let me just tell you a little bit about Liana Meneese.

She is a liberation psychotherapist and identity navigation specialist, centering people of the global majority queer communities, adoptees and those navigating layered identities, often excluded from traditional care with the masters in clinical mental health and applied psychology from Antioch, new England.

She specializes in liberation, psychology and anti. Oppression therapy, integrating somatic abolitionism, psychedelic support, and systemic healing as a transracially adopted Afro-Brazilian black American queer woman, she brings lived experience to. Decolonizing Care. She founded transitional characters, a Pittsburgh based liberation focused practice, and she is a member of the hashtag not White Collective.

Beyond her work, she loves cooking, art, and life with her husband and their two toddlers, the only biological family she’s ever known. Well, welcome to the show.

Liana Maneese: Thank you for having me.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: You have an amazing bio to start with, and I can’t believe you have two toddlers.

Liana Maneese: It is intense. It’s the only word to describe it.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: The chapter that you’ve written in the book is called Interracial Relationships, How Anti-Blackness informs kinship and therapist responsibility. So, could we start by talking about your really interesting origin story? You say that you were… I know you were adopted, and in the book you say anti-Blackness combined with transracial adoption has proven to be nothing less And a lifelong journey of becoming through undoing the undoing of the internalized belief still plagues you to this day. You say, I’m still fighting those voices now as I write this. So, can you give us kind of a little bit about how you came to be adopted, and how that’s impacted you through your life?

Liana Maneese: I mean, so I think, first of all, every single piece, part of my life cannot be disconnected from that experience. Which is something that’s so interesting, because most people are like, you know, everybody is born.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: But we don’t necessarily think about it like that. But, like, my being born in the circumstances, have informed every decision I’ve ever made.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: So, can you say a little bit about the circumstances that you.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, it’s, so when I was… I’m what’s called a Peace Corps baby, so that was, like, what they would, you know, say when you’re… you had someone who traveled in the Peace Corps, and, you know, made some connections with where they were placed, and then adopted from there. whether right away or later, my mother was… I’m pretty sure it was, like, the first class of the Peace Corps, but she went to Brazil and where… and lived where I’m from, which is Goyagna Goyas, Which is kind of, like, I guess the closest area would be Brasilia, if people recognize the capital.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: reward.

Liana Maneese: inland, and she lived there, and her job was to take care of babies and mothers. That was, like, her job. So she, she lived there for many, many years, actually, and she was, she loved it. That’s all she even after, you know, I… we… I came into her life. So she was there for, many years, then moved back to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which is where I live, and met my dad, and they were married, actually, for 12 years. And my mom… my mother could have biological children, but she said… she always said, I never wanted to. I always knew I was gonna adopt. And then when they were done having a good time, you know, or whatever, they were going to concerts or whatever they were doing, they were definitely having a good time. They were like, alright, let’s do it, and my mom called. Her best friend, whose name was Issa, who lived in Brazil, and Issa’s brother was actually the… they call it the judge of minors. So all of the children who were unhomed would be in front of him first. So, he could literally, like, hand-pick, as weird as that sounds, a child that needed a home, and that’s what they kind of did. So I guess the first child was some, I think, a young girl who… I think she might have been blind or deaf or something, and then something happened, that fell through, and then eventually it was me, and then a couple years later, my sister.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: But why did they call you a Peace Corps baby? Just because your mom was in the Peace Corps?

Liana Maneese: Yeah, it’s kind of just, like, I think, a joke of, like, all of these white women that were in the Peace… and men, but mostly women who were in the Peace Corps who traveled and came back, or eventually adopted children from other countries. Time was rare.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Was… so both of your parents are white, even? Yeah. Okay. So the reason they adopted you was probably their experience of being in the Peace Corps in…

Liana Maneese: Yeah, my dad was not in the Peace Corps, but he was, like, he worked at a high school, and he was, like, very, you know, he’s very community-minded, and, you know, took… had no issues with any of it, and my… my mother was the one who was in the Peace Corps. But adoption then was… interracial adoption. And, and it was just not common. In the same way.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Especially Black children, I mean, certainly.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, and from Brazil. Brazil doesn’t have a lot of adoptees coming out of it.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: So what do you… yeah, I know, we talk… we hear a lot about adoptees from China or Korea. That seems to be pretty common, but not so many from Brazil, for sure. But when you talk about this undoing of internalized beliefs that plagues you to this day, can you tell us a little bit more about that journey that you’ve been on?

Liana Maneese: It’s like, oh my gosh. Yeah, I’m just thinking, wow, where to start? Because there’s… there’s so many moments as I get older that now I have this awareness of what was really happening in those childhood moments that I didn’t realize until later, which I think is the undoing. And I think the undoing comes from my background before I, you know, got into the psych world. I was an anti-racist educator for many, like, 15 years.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Interesting.

Liana Maneese: I mean, I technically still do it, and that concept of undoing, right? You’re undoing these learnings comes from that. And… You know, when you grow up in… not only in a white household, but in a white supremacist, country environment, you… you know, there’s… you know, I got here, and I imagine as a child, you know, I always knew I was adopted, because my family didn’t look like me, so I, you know, and they were… like, nobody was hiding it from me, even though that’s a thing people do. But I didn’t fit in… at all. And I was very aware of it very, very early on in my life. extremely aware. Whether it was just, like, my neighborhood, or my own family, and I actually felt most comfortable with my mom and my dad, but my extended family, it was a… it was… very scary at times. You know, I was very aware of those differences and, ways of seeing the world, and the way that I was seen, treated differently, unseen, really. And… and then also, you know, during that time, there’s… there was so much placed on, the body. So I think, for me, a lot of the… the… of what I mean in that statement is actually related to my body. Not just in terms of the way that I looked, but, like, you know, this was Kate Moss era, skinny. You know, 90s, you know, there was… I remember there were what we would call dark-skinned, light-skinned wars going on, that’s what they called them at school. You know, there was a lot of internalized racism being worked out for everyone, and I think, for me, I had a particularly hard time because I was, like, very confused about who I even was. No one in my family or my community even called me black. It wasn’t until many years later, when I was actually, like, well into my adulthood,

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Hmm.

Liana Maneese: Somebody referred to me like that without me saying anything. And I remember that moment, because it was so intense. So I think, like, just not really knowing, like, who… everything is about what people are placing onto you, and, you know, in order to figure out, like, who am I? What is going on here, you have to undo all of those messages. And of course.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah, I’m sorry, you said in the chapter that you also had kind of a mistaken idea of who your birth mother was.

Liana Maneese: Yes.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: And that that has to kind of be undone. Can you tell us a little bit about that? Yeah.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, yeah, so… so this is just such an interesting… You know, psychological phenomenon, you know, of how we… process here, but I definitely had this idea of my birth mother as this, you know, like, what people would say, you know, certainly not my family, but what other people would… say about women who are, you know, of color in other countries who don’t keep their… don’t keep their children, you know, as, like, whores, or prostitutes, or these types of… this type of language, you know, that there was something, like, inherently bad that led… about them that led to the circumstances, and it was never something systemic, always something… an individual, you know, an addict, maybe, right? Or something… messages like that. And I had said something like that to my mother at some point, I don’t really remember if it was in an argument or what happened, and she flipped out. She was just like, what are you doing? talking about, but I really believed that. Like, it wasn’t like I was trying to be me. I, like, really believed that that’s where I came from. And she said, you know, we don’t… we don’t really know, honey, like, we don’t… I don’t know where that came from, like, that is not true, and, you know, we don’t have a lot of information, but… You know, she was like, this is just because, you know, there wasn’t a lot of money, and we know your mother loved you, and she took you, you know, to someone to try to… care for you, and… you know, she was just kind of trying to undo all of that messaging, but I… I still, to this day, like, have no idea where that came from, and I imagine it came from, you know, my environment somewhere, or something…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Even in movies and TV, you know, women, especially Black women or women of color who give up their babies are these addicts, or…

Liana Maneese: Yes.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Or their children were taken away from them for various reasons, so… Right. It makes sense. It’s just interesting that’s what you kind of inter…

Liana Maneese: actually verbalized as, like, a belief. Yeah, yeah, yeah, and it just goes to show how much all of that matters, right? It matters. Those messages, the representation, it really does make a big difference in how people kids, right? I was a kid when this happened.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Did you internalize any sense of that there was something wrong with you, and that’s why your mother gave you up?

Liana Maneese: I think that that is sort of this automatic… Thing that happens almost, biologically, you know?

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Kids really want to please their parents, right?

Liana Maneese: They all do, even if their parents are awful. They still have this deep desire to please them, and… so absolutely, I had internalized that, you know. I could have done something differently. Even though I consciously knew, you know, I was a baby, like, what was I really gonna do, but absolutely, I still feel like that, and I think I feel like that, too, because I’m like, you know, nobody came looking, not like they were gonna really be able to find me. There’s not really information that you can find there. But I think… And especially if they were very poor.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: If they were too poor to raise you, how would they travel to the United States, or whatever it takes to find someone?

Liana Maneese: Yeah, but definitely, I think that’s internalized for sure.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Okay. Yeah. So, I know you said that you’re a… or in the bio, it says you’re a liberation psychologist. liberation psychotherapist and identity navigation specialist. First of all, those words are really interesting, but what does it mean in terms of what you do on a day-to-day basis?

Liana Maneese: Hmm. So that’s a good question. So, like, liberation psychology is really interesting because, I learned about it actually in anti-racist studies. So I taught it, but as an anti-racist educator before I got into the psych world. So I knew that that’s what I wanted to do when I came into the psych world. I was like, that’s the world, that’s what I want to focus on. And, you know, liberation psychology is really, I guess sort of like the antithesis of what we think of as, like, Western psychological practice, you know? It really emerged in Latin America, so I also felt that connection to it. And Ignacio Martin, I sometimes say his last name wrong, Barrel, I think, was the founder. He was murdered by the CIA, which also, I feel like, is important, because that’s how, you know, we would say radical, but it’s like, it’s not really radical, right? It’s like… but we would say, you know, because he was, you know, he was a radical, he was… he was a leader, you know, in terms of, that really fostering a critical consciousness and an awareness of the collective Fight for justice and liberation, and action. oriented, An action-oriented way of being in the world.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: And so I’ve deeply connected to that. And so when I started my, practice, I had to think about, yeah, so what does that actually look like in practice? You know, because you know, I think the powers that be, you know, they still see this as sort of just like a modality, you know, it’s just like another, like CBT, or, you know, any sort of, like, act, or some sort of modality that you can sort.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: We are, yeah. Yeah. But of course, I don’t think that way at all. I think it’s, like, the… the… it is… I think of it as this completely very separate thing that we’re doing, that It sounds like it’s more like the ground that you come from, the place that you come from. Like, most therapists are white, or they’re not Black, and or even Latinx, or whatever, and so they come from the culture that.

Liana Maneese: which is the dominant culture, you can’t help it. Yeah.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: you’re saying that the place that you come from is a different place, but how do you still decolonize your internalized, you know, views and experiences growing up in America? It’s a white supremacist society.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, yeah, totally. So, I mean, I think it’s like there’s this everyday, practice of, well, what does it mean to do these things and have these beliefs? be working on it yourself, simultaneously, as you’re working with other people, and then also to have this business where you’re trying to create structures that are rooted in justice, right? So, a lot of it is, like. I think a lot of what I do is, first, sort of revolves around, what I would call, like, white supremacist sort of characteristics. So, there’s a list of characteristics I’m happy to share with you, and we can, like.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: in.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah, well, just give us a few right now, and then we can…

Liana Maneese: Oh, sure, like, perfectionism is one of them, like, sense, a constant sense of urgency, this, there’s one way to be right, or one way to do things. So there’s a whole sort of list of these sort of characteristics. And so, I think one of the first steps that, I work on, or worked on personally, was recognizing those sort of characteristics in myself. And when they pop up, how they pop up. what that meant for me in different environments, like at home, at school. I really struggled in school. Not necessarily academically, but I struggled Sort of in all the ways, just, like, even being physically there, to the point of, you know, I got in a lot of trouble. I got 302’d, I didn’t want to go to school. So it was really challenging for me to, to… to understand. you know, even once I had read a lot of books, and I knew what was going on, and I knew how to recognize racism to some extent, I still didn’t know how to implement these practices in my own life. So… and honestly, I still don’t have all the answers, like, I still don’t. I think I’m… I think I have these… these… these things that are… still very much a part of me, and more so than trying to just fix them or expect them to go away. It’s more about accepting that this is part of who I am, and how I was raised, and my circumstances, and now it’s more about recognizing, learning to recognize it, and try my hardest to redirect or correct. It shows up in me in… in ways that are rela… I’m very hard on myself. Like, extremely. And I think that is probably one of the biggest challenges that I’ve had personally that… that… deeply affects the way that I move. And then there’s that personal side of it, and then there’s how do we do this with clients? How do we do this with the people that work here? And a lot of it is really education. A lot of it is education, a lot of it is having real conversations about self-awareness and how to recognize some of these behaviors. But really just a lot of education and a lot of conversations.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: It actually sounds like it combines your two careers as a… Oh, for sure. Yeah, which is really cool. And I would imagine, as a patient, that patients who come to you feel much more comfortable talking about things like microaggressions and so on. I’ve been in therapy most of my adult life, on and off, and as you’re talking, I realize I’ve never really gone to any therapist who I felt comfortable talking about, you know, being microaggressed, or being… you know, I had someone in my, friend group kind of challenge what? Why I say that I’m black. Both of my parents are Black, you know, I grew up during segregation, Jim Crow in the South, so I went to segregated schools until high school. So I have, you know, I mean, I am deeply part of Black culture, and Black culture is deeply part of me, no matter how I look.

Liana Maneese: Yeah.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: But she… her… her point was, oh, well, you should call yourself biracial, because you don’t look black. You know, or… and you wrote about some of the things that happen… have happened to you in the same way. You know, people asking you, what are you, or… you know, had somebody say to me, oh, you have the same voice as this character on TV, which was a Black woman, so yeah, we are both Black women, but she had a strong, like, New York, Brooklyn accent. I don’t have that accent, so… So, I just don’t get it, but again, I never had a therapist who I could discuss these things with.

Liana Maneese: Well, those are great examples of exactly, I think, what I mean in the chapter. Are these, like. you know, I mean, we say microaggressions, and I don’t think they’re very micro, right? They’re very aggressive, like, excuse me, you don’t get to have an opinion about this at all, but I think that it’s like this, people need to know who you are, because they are trying to figure out where… who they are. Like, they don’t know who they are. So they try to figure out who they are based on how other people experience them. You know, and part of that is them trying to categorize and organize others, because that’s how they categorize and organize themselves. And so much of that undoing, right, is separating yourself from that.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Also, their need to be right about it.

Liana Maneese: Right, which is a… which is a white supremacist characteristic, right?

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: That’s what I’m learning from you right now, so that’s very interesting, because you can say, well, here’s this, that, and the other, and they’re still like, no, your voice sounds like, no, I’m not even…

Liana Maneese: Everybody’s voice sounds like all kinds of things all over the world.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yes, right, but mine doesn’t sound like a Brooklyn accent, I can tell. I would love to have one, I think it’s pretty cool, but…

Liana Maneese: I mean, people make up a lot of stuff, and also, you know, people project a lot of things onto Black women. And I think that’s one of the most fascinating conversations in the anti-Blackness canon of conversation, right, of things to address is the amount of ways that people use our bodies to project their own trauma, their own fears, their own, whatever.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Right, yeah.

Liana Maneese: And it happens…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Do you think that is ancestral? I’m just thinking… when Black women were enslaved, that many took care of white children and raised them, and it’s always this kind of thought that, you know, the strong Black woman meme, and, you know, do you think that in the white psyche, that there is this sense of, you know, that something from that ancestral time that makes people think that they should, you know, Black women should be more nurturing, or Black women shouldn’t be angry, or fill in the blank.

Liana Maneese: I think that it’s more related to people’s own sense of… or lack of… resilience and lack of their own understanding of their own, sort of, power. It’s… I think it’s, like… It’s like a… it’s like a… it’s… it is psychological, you know, and it is absolutely this sort of… even… something that probably, you know, should be pathologized in some way, but this, like, this process where people attribute their own unconscious, unacceptable thoughts, feelings, about themselves onto us. And I think that it is rampant. I think that it is absolutely, part of how racism is shaped, not just, you know, in America or through enslavement, but, you know, onto people of color all over the world. It’s… when you think about whiteness, right, and we’re seeing it now currently in our society currently, it’s always a flip, right? It’s a… it’s, it’s not me, it’s you, right? There’s always this, like, you know, this is… this is… all this violence is happening because of you, even though… the U is not inflicting any violence on anybody, right? But it’s still… you know, you’re the violent one, you know? The Black people are violent, the women are violent, we’re aggressive, you know, you deserve this treatment from, you know, these other groups. And that is absolutely this, like, you know, the projection onto Black women that is rooted in… it is a defense mechanism, right, from owning your own Lack of understanding, lack of knowledge, lack of… You know, really… everything, you know, because it’s like, clearly you’re missing a lot here, but it is a defense mechanism, and it’s total scapegoating. It’s absolutely a way to just escape any responsibility for your own, disconnection, to the, you know, the harm that these people are doing, and so they enact these archetypes and stereotypes onto us.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: Yeah.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: It’s… it’s really fascinating, interesting to watch, and to… when you are aware of it, to see it play out, you know, so many ways. So, as part of that, one of the quotes from your chapter is, the very nature of asking a perceived racially ambiguous person what they are is anti-Black rhetoric rooted in the dehumanizing of Black people. What implies you may not be human at all? This is what, oh, I’m never going to be able to pronounce this And the guy who did this. It’s Zhao H. Costa Vargas, maybe? I hope I’m not mispronouncing it too bad. It’s what he reminds us is the very expulsion of Black people from the human family. So, I just… I thought that really sums it up a little bit. So, another… thing that you wrote in the book is you say, in interracial relationships, we are dealing with layered identities, not just simply white and black racial differences, but the manifestations of anti-Blackness in each of us pertaining to similarities and differences.

Liana Maneese: Yes.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah. Okay, so in your work, you’ve been very vocal about addressing anti-Blackness, both within and outside of Black communities. How has your life experience across race, family, and love shaped your understanding of how deeply anti-Blackness… anti-Blackness operates?

We have to take a big breath on that one. I saw you.

Liana Maneese: Can you repeat the question? I hope you have it written down.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yes, I can repeat the question.

Liana Maneese: Okay, thank you. Because I was like

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: I know it’s heavy. It’s a heavy question. Okay, so you said in your work you’ve been vocal about addressing anti-blackness.

Both within and outside of black communities, how has your own life experience across race, family, and love shaped your understanding of how deeply anti-blackness operates?

Liana Maneese: I… so, you know, I think the reason why in this chapter I wanted so badly to focus on Kinship and relationships is because that is where it hurts the most. You know, because… you know, we’re surrounded by these things all the time, you know, and some of us recognize it, and some of us don’t, you know, as it’s happening, or we recognize later, we get home, and we’re like, oh my gosh, that’s what they were doing. But when it’s in your own home, it is…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Even among friends that you’ve…

Liana Maneese: Oh, yeah, even among friends, yeah. People that you believe care about you, or that you care about, you know, that don’t see how this stuff shows up. And when you… when I was doing anti-racist work and started really doing that and learning what this stuff really looks like. Actually, and how to recognize it. Of course, I saw it everywhere, all the time.

And then I was so hurt.Because all these people that I had on these pedestals, including my parents. I had to be like, oh… Even… even in love, this doesn’t…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Go away.

Liana Maneese: away. Yeah, it doesn’t go away. And not only does it not go away, most people are too defensive to even be interested in hearing what is actually happening, or adjusting, which is, of course, what I see in, you know, the work that I do, especially in families, you know, and parents who don’t want to see those differences.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: I’m not racist, you know.

Liana Maneese: I’m not racist.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: I adopted a child from Brazil, you know, I’m not racist.

Liana Maneese: Yeah. Right. All of those things are used as, as… yeah, as… well, again, we’re scapegoats for everything, right? And it’s like, you get this automatic badge of goodness, you know? Even if it’s not a kid of color, I mean, if you adopt a kid, no matter what color they are, even if they’re white and they look like you, you are a martyr somehow, right? You are above all question. And a lot of these people are actually very violent emotionally, which we know and see constantly when you work with adopted and fostered children, you know? They’re lucky enough to go somewhere, that is… that is not their experience, but it is even in the best, and I want to stress that I’ve probably had pretty close to the best situation. I mean.

My parents were extremely, extremely intelligent, extremely aware and knowledgeable of the world and what was going on historically and what was happening currently. They considered themselves anti-racists, they were activists, you know, we had a very diverse group of friends. You know, I had a very good situation. I grew up in a black neighborhood, even though my parents were white. You know, I had…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah, it does sound like the best case scenario

Liana Maneese: It was a best-case scenario for sure, and still, there are so many painful moments. And I can give you a couple of examples, like, I don’t remember if I said this in the chapter or not, but, you know, I did write an article about it, when this happened. The first time Trump got elected years ago, I had… I lived in a very, I mean, very famous sort of black neighborhood at August Wilson’s neighborhood. It’s called the Hill District in Pittsburgh. And there had actually been this white nationalist, like, parade sort of thing that had gone through our neighborhood. There were swastikas on the trees. I mean, it was very scary when this happened. I didn’t leave the house for a few weeks, told my husband I was just, you know, I was really nervous, and then finally I decided to leave the house, and I wanted to go home, of course. I wanted to go see my parents. That… I get home, and my dad starts kind of going on and on about, you know, how Black people didn’t vote for Bernie, and that’s why we lost.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: He’s literally blaming Black people for.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, there’s no awareness of my identity in the moment, right? And then there’s also no awareness of, like, like, what are you talking about? Like, what are you, you know… It’s like this… it is just such a good example of how when the pressure gets high, even, you know, and it is a liberal, you know, now people are talking a lot about this, but I was raised very much to understand the difference between a leftist and a liberal. And I consider myself, my parents, to be very left, you know? But not left enough.

But maybe, you know, but I… and again, you know, there is a gen… a large generational difference, you know, my mother would have been in her 80s now, you know, so… so in their time, they were, whoa, way left, but… so I don’t consider them, like, liberals, but they certainly are in between sort of a liberal and a leftist, because there… there was not… an awareness when that stress came of who they were taking it out on. My father, at least in this particular case, who I have a very good relationship with. I loved my dad, I was a daddy’s girl all the way, we were very close. And these moments crushed me. That was one of the first times in my adult life that I was like, I’m gonna take myself into an institution. I was so hurt after the argument that ensued after that, because I felt so unseen.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: And so he… he became defensive, I’m assuming?

Liana Maneese: It turned into a very nasty, nasty, scary… fight. I got kicked out of the house, and it was, my mother didn’t really defend me at all, and I felt like I was fighting to be seen. Like, do you know who you’re talking to? You can’t even hear what you’re saying. Like, I… I was so deeply traumatized by that, situation. And then my father, you know, he doesn’t talk about anything, right? Which is another trait of another podcast conversation, but another trait, you know, where it’s like, you know, he… we just don’t speak until… he’ll never apologize, but then he called me, like, weeks and… you know, he’ll call weeks and weeks later and say, hey, I found something you were looking for, or, you know, just using something to kind of reach out, but never an apology, never an awareness of the severity of what happened, and I think he sees it definitely as just, like, you disrespect your…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Elder.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, you disrespect your elders, and that’s the kind of, you know, things that happened. You know, my… I think I wrote this in the chapter, you know, my husband’s father, my husband is Chinese, his father is white, and his mother is from Hong Kong. And, you know, they threw the N-word around at the table, his father.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: What?

Liana Maneese: Yes, we were talking about, you know, the economy. And this man said, you know, we’re all… Basically, this is a white man saying that we’re all N-words, because we’re all slaves under this system. And I’m just… I was like… And this is very early on in our relationship, okay? And we’ve been together, I want to say, 14 years now, with 2 kids, we got married 5 years ago. And this is very early on, and I went… I just kind of sat there. I couldn’t believe it.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: And then I just got.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Sometimes it comes out of the blue, and it catches you unawares, you know?

Liana Maneese: Well, and his mother sat right at the table and was watching the whole thing. Her face didn’t even flinch, which tells you something.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Definitely, yeah, yeah.

Liana Maneese: Yeah, and yeah, so these are…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Did you ever go back and address it, or no?

Liana Maneese: oh, we… we said… we didn’t speak to them for nearly a year, maybe longer. We said, if you… you need to go to therapy, you need to see someone, we need… this is… we’re not okay with this. It was very serious, and it gets worse. Because his father finally did agree to see a therapist, went, and at one point invited my husband to come and… could come to a therapy session. I remember my husband was actually kind of excited about it, like, I’m happy to talk about this. He wrote a list of the things he wanted to talk about. He gets there, the conversation around the N-word comes up. This white therapist, man, says, in the conversation with my Chinese husband and his father, says, well, I wouldn’t have said the N-word with an R at the end. I would have said it with an A. Hahah, haha.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Oh, no!

Liana Maneese: Yes. Yes.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Oh my gosh! compounds every.

Liana Maneese: Yes, and that is probably one of the major reasons I am here in this seat. that work, because of the trauma that is caused, you know, because everyone wants to say, it’s like, oh, black people and brown people, we don’t go to therapy because it’s not in our cultural… you know, they put it on us, and it’s like, huh. No, it’s because look who is doing that job!

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah.

Liana Maneese: Looks like us, people would come to therapy.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah, like I said, 30-some-odd years of therapy.

Liana Maneese: But they want us to believe that.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: I never talked about racism, you know, in my therapy.

Liana Maneese: Yeah. So, I mean, these are things that happen constantly, and again, these are liberal people. These are people who consider themselves… this is a man married to a woman from Hong Kong, married to a Chinese woman. So there’s no thought, right? There’s no thought into this concept of what it means in an interracial relationship, and what that really looks like. And to be honest with you, a lot of people I see in interracial relationships that come to me with issues don’t make it. Because once they really understand, The tokenism and the defensive… The defensive behavior that comes when you really start to recognize these things doesn’t tend to go very well.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah. I’d like to talk to you for days. You have a wonderful, interesting career, but I want to wrap it up, because we’re almost out of time, and just ask you if you could kind of imagine, like John Lennon, imagine… what a truly liberatory healing space looks like, whether it’s therapy, or community work, or relationships. What would it feel like? And… How close? is… your group. To building such a community or such a space.

Liana Maneese: I think… I think it feels… like… Not quite there, but very close to loving yourself.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: It’s really with… it starts with you.

Liana Maneese: Yeah. I mean, that’s what’s taken from you, right? Your humanity, your dignity, right? These are the things that are taken very young, and a lot of people don’t even realize, they think they have these traits, you know? I do love myself, like… But most people do not have these…

And it’s not, you know, it’s not your fault. This is… you’re not supposed to in a society that… that looks like this, you know? It’s supposed to be taken from you, and this is… you’re supposed to be a worker bee cog in the system. So I think it’s, so I think that’s what it feels like. I don’t know what it feels like to… to be there, and I don’t know if it’s realistic to get there, completely, but I know it feels like that. as I imagine it to be. And then in terms of my… of getting there, absolutely, I feel like we are on the way, as a group. That’s one of the reasons why I started this, because I had met a number of therapists as individual people who were amazing and very liberatory, you know, very focused, very decolonial in their practice. But none of them worked for groups. And if they did work for groups, they didn’t feel protected to be… to enact those… things in their sessions, you know? And if they did, which we saw after October 7th, a lot of people got fired, pushed out of their jobs, all of that type of, you know, thing. So I think that creating a space where people felt, safe to really live the value of liberation and anti-racism as it truly is, and then also recognizing that we can’t I can’t just, like, snap my fingers and everybody’s Latino and black in our field, that’s ridiculous. So I think creating a space where there is a diverse group of people, where we’re all still rooted in our value system, and then.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: And where you can learn together, even.

Liana Maneese: Yes, yes, because I want someone like me, who may not be able to get a therapist that looks like me, to still access somebody that they can talk about microaggressions and they know what they’re talking about, and they have awareness of what they’re saying back, and they have a boss that looks like me that’s telling them, you know, boss, I mean, whatever that means, you know, in private practice and, you know, but, like, somebody who has the expectation Of that level of excellence in your understanding of… of navigating racism and, you know, and colonial harm. And that’s my expectation of everybody here.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: And I think also the ability to just.if you’re wrong, to apologize and repair.

Liana Maneese: reflect, yes. Yeah, and to self-reflect and say, well, I did that wrong, and I’m coming back. You need training. I mean, you have to have a space to be able to train people. They don’t teach you this stuff in school, even though it is a technical modality, and there’s psychological books written about it. You need a place where people can come and learn. how to do this, and that’s our goal. We want to be a space of learning, and we want to spread, some offices around the country so that we can start exposing people to liberatory work.

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: That’s wonderful. Well, it’s been just very interesting and educational to talk to you, and I’m sure anybody who listens to this podcast will gain a lot from you. So, Liana Maneese, thank you for being on Inclusive Minds, and God bless you and your work.

Liana Maneese: Oh, I appreciate you so much. Please stay in touch, and I’m happy to send any links, or… and I’m very accessible, so you can share my email, or whatever. I… I love meeting and talking and learning, and…

Dr. Carolyn Coker Ross: Yeah, and please share your list, the primacy list, that would be awesome. We can put it in our show notes.

Liana Maneese: Yes, I’m so grateful for you and everybody listening. Thank you so much.