The use of substances for relief and pleasure isn’t new—it dates back thousands of years. But what’s striking today is how the misuse of one category of drugs—opioids—has evolved into one of the world’s most dangerous public health crises. Across the globe, more than 26.8 million people live with opioid use disorder (OUD), and over 100,000 opioid overdoses occur each year.

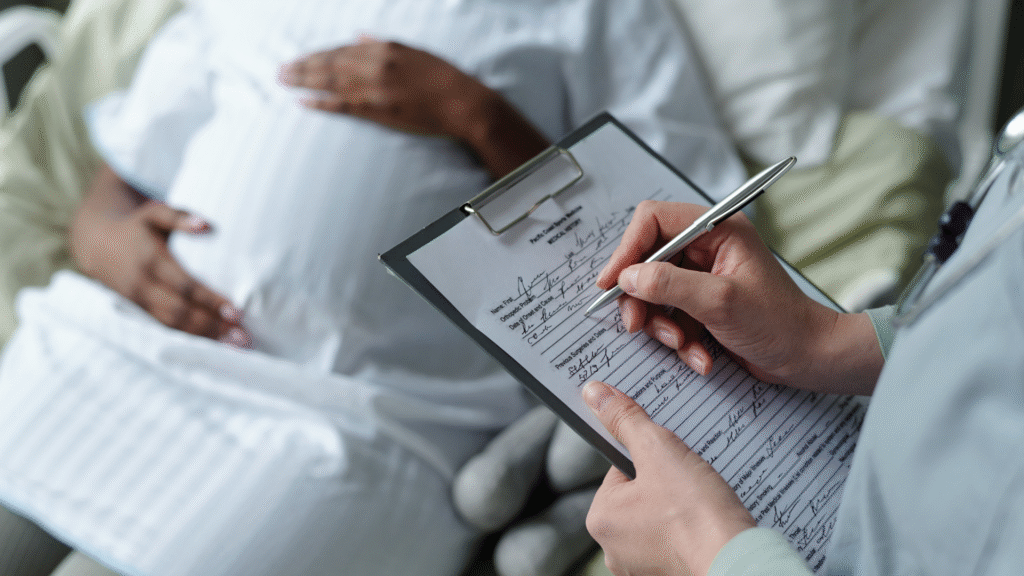

Behind those numbers are real human stories—of parents, teens, and, critically, expectant mothers navigating stigma, systems, and survival. When we talk about maternal health, the conversation now must include OUD. Because for many women, pregnancy doesn’t protect them from addiction—it complicates their path toward recovery.

The Rising Tide: Opioid Use in Pregnancy

Rates of opioid use during pregnancy have climbed dramatically, mirroring trends in the general population. About one in five women fill an opioid prescription during pregnancy, while around 5% use illicit drugs, a number that has quadrupled since the late 1990s.

The consequences can be devastating. Pregnant women with OUD face much higher risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, stillbirth, and neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS). These risks aren’t just biological—they’re often compounded by chronic infections, trauma histories, and inadequate prenatal care.

A Lifeline: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD)

The good news? Evidence-based treatments work. Medications for opioid use disorder—such as methadone and buprenorphine—can stabilize cravings, reduce overdose deaths, and dramatically improve both maternal and neonatal outcomes. For many expecting mothers, these treatments are life changing.

Despite this, fewer than 20% of pregnant women with OUD actually receive MOUD. Why? The barriers are complex, deeply entrenched, and often beyond a patient’s control.

Barrier #1: Stigma and Fear

The most persistent barrier is also the most invisible—stigma. Many pregnant women with OUD delay or avoid care out of fear. Fear of judgment. Fear of being labeled a “bad mother.” Fear of losing custody of their child.

A recent review found that fear of Child Protective Services involvement is one of the strongest deterrents to seeking treatment. This fear often outweighs a woman’s motivation to enter care—especially when she’s been told that methadone or buprenorphine will “harm the baby.”

In truth, research consistently shows the opposite: infants born to mothers on MOUD fare significantly better than those exposed to untreated opioid use. Education rooted in compassion—not fear—can change these outcomes.

Barrier #2: Economic Hardship and Red Tape

For many mothers, recovery isn’t just an emotional struggle—it’s a financial one. Studies show that unstable insurance coverage and high treatment costs are leading barriers to accessing MOUD.

Low-income women, especially those on Medicaid, often face inconsistent coverage, high deductibles, or prior authorization requirements that delay treatment. In some states, methadone isn’t even fully covered by Medicaid—a policy gap that directly affects maternal and infant outcomes

Policies expanding continuous Medicaid coverage beyond the postpartum period could meaningfully improve maternal survival and reduce relapse rates.

Barrier #3: Provider Hesitation and Knowledge Gaps

Even when women are ready to seek help, the system may not be ready for them. Many obstetricians report feeling unprepared to treat OUD, citing limited training in addiction medicine.

Without standardized protocols or clear communication pathways between obstetric and addiction specialists, pregnant women often fall through the cracks—referred elsewhere, delayed in care, or given inconsistent guidance

Education can change this, too. When providers receive targeted training on trauma-informed and recovery-oriented care, both treatment uptake and patient trust increase

Barrier #4: Structural and Systemic Challenges

Access depends heavily on where a woman lives. Geographic and systemic disparities mean that rural patients face longer wait times, fewer clinics, and less availability of MOUD**.

Even in cities, logistical challenges—transportation, lack of childcare, rigid clinic hours—make attending daily methadone appointments unsustainable. For a pregnant mother juggling multiple responsibilities, missing a dose might mean relapse.

The proposed solution? Integrated care models that combine obstetric, mental health, and addiction services under one roof. Studies show that co-located services improve engagement and retention—69% of women remained in MOUD through the postpartum period.

The Overlooked Factor: Intimate Partner Violence and Social Pressure

For some women, the barrier is much closer to home. Intimate partner violence (IPV) affects decisions around treatment, especially when partners limit access to care or discourage medication use. Emotional or financial dependence can make it nearly impossible to prioritize health.

Compounding this, family or community disapproval may heighten shame and isolation Medical recovery is essential. But so is social recovery, requiring safe relationships and systematic support

Turning Insight into Action

While the barriers are extensive, they are not insurmountable. The research points to several clear opportunities:

- Normalize universal screening and early intervention. OUD screening should be routine at the first prenatal visit, delivered in a nonjudgmental, trauma-informed way

- Expand Medicaid and insurance coverage beyond 60 days postpartum to ensure continuity of care

- Train providers across disciplines to recognize, manage, and treat OUD confidently during pregnancy

- Integrate care delivery—link obstetric, addiction, and mental health services.

- Support women holistically by offering childcare, transportation, and family-oriented recovery programs

Each of these steps transforms numbers into outcomes—reducing overdoses, improving neonatal health, and restoring dignity to mothers navigating one of the most stigmatized conditions in modern medicine.

Final Thoughts

Behind every statistic on opioid use in pregnancy is a woman trying to survive—often in a system that wasn’t built to support her. OUD during pregnancy isn’t a moral failing; it’s a treatable medical condition. When communities, policymakers, and providers come together with empathy, education, and evidence, they create a lifeline for both mother and child.

If we commit to breaking down stigma and building up care access, we don’t just improve outcomes—we change lives, generation by generation.

As leaders and change agents, we have a mandate to move beyond awareness and into actionable policy reform.

Where is the biggest policy gap in your state or organization currently failing pregnant women with OUD?

Let’s discuss tangible steps to integrate care, expand Medicaid, and dismantle the structural barriers that cost mothers and infants their lives.

Connect with me to schedule a strategic consultation on transforming your maternal health and OUD protocols.

#WomensAddictionTreatment #GenderSpecificCare #SubstanceUseDisorder #WomenInRecovery #TreatmentEngagement #WomenCenteredCare #OvercomingBarriers #AddictionRecovery #HealthcareEquity #TraumaInformedCare