Taking a different perspective on addiction, Dr. Gabor Maté believes that addiction has a lot to do with how people experience life in their early years. He attributes it to the adversities one goes through during childhood. Dr. Maté is a physician and bestselling author whose interests include mind-body unity, health illness, and the treatment of addictions. With this background, he talks about addiction in light of the mind-body unity, how it connects with the experiences we go through in our environments, and how it is manifested later on in our thought process, developing traumas. He debunks the idea of addiction as genetics and discusses how attachment affects the brain.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Dr. Gabor Maté: How Mind-Body Unity Affects The Development Of Addiction

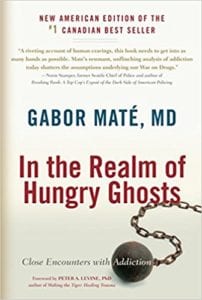

In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction

My guest is Dr. Gabor Maté. He is a physician and bestselling author whose interests include mind-body unity and health, illness and the treatment of addictions. He regularly addresses health professionals, educators and lay audiences throughout North America. He’s a gifted psychotherapist. He leads transformative seminars several times a year. He has worked in family practice, palliative care and addictions. His book which we’ll be discussing on this show is called In The Realm Of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters With Addiction. It won the Hubert Evans Prize for Literary Non-Fiction. Welcome to the show, Dr. Maté.

Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

It seems like your interest in medicine are pretty varied. How did you begin to work with this population who had addictions in Canada?

I live in Vancouver where there’s a neighborhood called the Downtown Eastside, which is generally notorious as North America’s most concentrated area of drug use. Within a few square block radius, you have sums of people who are dependent on injectable substances heroin, cocaine and crystal meth and alcohol, tobacco and other drugs. I’ve been in practice for many years. I had some addicted clients in my practice. At some point, I also got interested in attention deficit disorder with which I was diagnosed at age 52 and that was my first book. ADD is a major risk factor for addictions. What struck me through my medical practice is that childhood experiences, particularly of a diverse kind have long-term effects on people. Outcomes such as cancer and rheumatoid arthritis, ADD and mental illness in general and addictions specifically has a lot to do with how people experience life in their early years. That consciousness began to dawn on me more and more as I pursued my medical career. At some point, I just had this call to work with that particular population all the more so since not only did I see them as the people most needing medical care in our society. I recognize in myself many of the same patterns that I saw in them. It was both a medical inspiration I suppose that drew me to that population, but also the knowledge that I shared some of their dynamics.

Can you say more about what you saw as the dynamics that you shared with that addiction?

At the heart of addiction, all these are intrinsic emotional pain and nobody chooses to be an addict. Addiction is an attempt to solve a problem, not to get one. The problem that the addiction is designed to solve or at least unconsciously intends to solve is the problem of emotional distress and pain. A sense of insufficiency and emptiness that you try to feel from the outside. I haven’t done that in my own life with substances, but I certainly have done it with behavior such as work and shopping. That distress and that emptiness I can certainly relate to. It’s just that the clients that I ended up working with who are dependent on heroin and cocaine would have the emptiness and the pain in higher degrees than I did and that was the only difference.

From your point of view, it’s just a matter of degree?

Addictions are located in a continuum that one sees throughout our society. When you look at the addictions, whether you look at the brain biology, the brain physiology or the psychological dynamics, it’s very similar to whether you’re a workaholic or whether you’re a heroin addict. Whether you’re a gambler or whether you’re dependent on cocaine. These are matters of degree. If you look at people’s lives, matters of degrees of suffering I suppose.

Is your understanding or your view of addictions different do you think from the conventional view which holds that you know it’s a genetic issue that causes addiction?

The broadest social view is not even meant as genetic. Society looks on addictions as a choice that somebody makes. Hence the punitive response to it. If somebody has a genetic disease, why put them in jail? The fundamental belief that drives social attitudes and the war on drugs and the whole legal approach to addiction is that this is a choice, a bad decision. That somebody deliberately makes that need to be either deterred from it or punished for it. The medical perspective is more that it’s a genetic disease that runs in families. You inherit the gene and then you’re going to be addicted. I don’t see it that way at all. There might be genetic predispositions, the common factor in our addictions and the research is not even controversial. It’s clear that the more adversity you experienced in childhood, the greater the risk of addiction. In the Downtown Eastside where I worked in my many years of work with this population, I never met a single woman who had not been sexually abused. The men had all suffered degrees of abuse and sexual, physical abandonment and neglect. All kinds of trauma, not just one time but repeatedly throughout their childhood. That for a whole set of reasons then sets up the predisposition to addiction. Any genetic factors that may be present are superseded by the environment. Studies have shown for example that even in children who may have some genes that predispose to addiction, if they’re brought up in a nurturing family those genes are not expressed. Those genes are not activated. The key factor is never the genes in addiction. My profession and your profession, the medical profession is addicted to the genetic perspective for a whole lot of reasons.

[bctt tweet=”Addiction specifically has a lot to do with how people experience life in their early years.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]Why do you think that is because it’s puzzling to me?

Our society has a bad misunderstanding of the twin studies that butchers the genetic perspective. More than that, you as an integrated physician will probably agree with me that the medical profession by and large, despite the scientific evidence, still very much separates the mind from the body. It separates the individual from the environment. Rather than seeing that human beings develop from conception onwards and remain until death in a dynamic interaction with the environment, typically the psychological, social, emotional environment, we see them as discrete individuals. Rather than seeing the source of these problems in a person’s relationship with the environment, we see them in the individual as if they’re separate from that environment. You’re left with genes. That’s one reason, that mind-body separation. We separate the individuals from the environment. We also separate the individual internally into a collection of organs, rather than seeing that emotional lives and/or organic processes are completely intertwined. They can’t even be separated either theoretically or biologically in a live person.

The most shocking part of medicine for me in the treatment of addictions is the ongoing stigma that’s placed on addiction. I have patients and friends with a history of addiction and family members and they may have been sober for over a decade. When they entered the medical system, they’re still treated like addicts and treated poorly.

Even if we believe that addiction was a genetically determined condition, then how possibly can we condemn people for it? What choice does any of you have of what genes to inherit? The moral judgment, the opprobrium that is cast upon addicts is very much based on this belief that people are choosing to be addicted. There’s a contradiction there. If it’s genetic, lets at least not condemn people for it. The reality is that it’s not even genetic. It very much depends on what a person’s life experiences are. If you look at my clients and the high degrees of abuse amongst that particular population, this is validated in large-scale population studies in the States called the famous Adverse Childhood Experiences Studies. If people who were abused and traumatized as children and if that then leads to certain lines of brain development and personality development, how can you blame people for it? Did anybody choose to be sexually traumatized when he was five years old?

Talk a little bit about the ACE Study because since it first came out, I found that to be a fascinating study and important.

If we took its implications to heart, we would have to change our whole approach to how we practice medicine. The Adverse Childhood Experiences Studies were performed in California. I know you were interested in eating disorders and the lead researchers were working in an obesity clinic. They found that with a rigorous regimen of diet and positive feedback, they could help people lose weight. They couldn’t help them keep it off. They did what medical doctors rarely do, they listen to the patients. Dr. Vincent Felitti was one of the lead researchers told me that one patient said, “Don’t you get it? I’m eating to soothe my pain.” He started gathering the stories of his clients. One story of trauma after another. The eating was people’s addictive attempt to soothe pain and to suppress the stress. That led to the Adverse Childhood Experiences Studies. An Adverse Childhood Experience is a physical, sexual or emotional abuse. It can be the loss of a parent, death, being jailed or a rancorous divorce. It can be a parent being addicted, violence in the family or mental illness in the family. They looked at 15,000 adults in California. For each of these Adverse Childhood Experiences, the risk of addiction went up exponentially. It went up two to four-fold. By the time a male child had six of these, his risk of having become an injection-dependent substance addict was 46% greater than that of a male child with no such experiences. That’s a 46-fold increase. The risk of smoking went up. The risk of addictions went up. The risk of obesity went up. The risk of eating disorders went up. The risk of autoimmune disease went up. The risk of cancer went up. The risk of antisocial behaviors went up. The risk of relationship problems went up. The risk of early death went up. Based on Adverse Childhood Experiences and most saliently the addiction was clearly shown to be related to the degree of childhood trauma.

Many people may be shocked though that adverse childhood experiences would be related to the risk for autoimmune diseases and cancer.

When the Body Says No: Understanding the Stress-Disease Connection

That’s the subject of another book of mine called When The Body Says No: Exploring The Stress-Disease Connection. Biologically, it’s not that shocking because you and I know that trauma is not just an emotional event in isolation from the body. When people are abused, it sets off physiological responses like an exaggerated stress response. With heightened levels of adrenaline and cortisol and all changes in the immune system. All changes in the neuropeptides, the chemicals that the nervous system secretes. It sets off lifelong patterns of coping that dysfunctional that people tend to suppress themselves in order to survive. That self-suppression then leads to immune suppression or immune attack against the body. Physiologically, it’s easy to understand if you look at the physiology, the biology and then the source of it. What is known that those early patterns set up, for example, children who are abused will have a lifelong tendency for inflammation, inflammatory particles in their bodies? A Canadian study showed a couple of years ago that if you’re abused, the risk of cancer goes up by the factor of nearly 50%. That’s not necessarily inevitable, it depends on how you deal with it and what kind of help you get. On its own, it’s a risk factor and it’s not purely psychological. It has to do with the fact that you cannot separate the mind from the body.

The fad in addiction treatment seems to be talking about attachment. What role do you feel attachment plays in addiction?

I’m delighted to hear that it’s a trend. Attachment is the emotional relationships between parents and children. That’s the key question in addiction. We know that the human brain develops an interaction with the environment, but which circuits develop and which do not have to do with environmental input. The biggest factor in that environmental influence on brain development is the quality of the attachment and relationship with the parents. The more stressed, distracted or troubled the parents are, the greater the difficulty the child will have in terms of brain development. If you look at the key circuits in addiction which don’t work in the brain so well, they are the opiate circuitry. The real internal opiates like we have endorphins, which are the body’s natural morphine-like substances. They’re called endorphins which means endogenous morphine-like substance.

The endorphin apparatus that we have is designed to soothe our pain. It’s designed to give us a sense of pleasure and reward. It’s designed to maintain our attachment to relationships. Attachment is a key because the human child, the human infant is the most helpless, the most immature and the most dependent for the longest period of time of any creature on earth. That means that without the attachment to relationship, we simply don’t survive. We can’t survive a day without our attachment to relationships when we’re an infant, even as adults we’re dependent on them. As infants and children, we’re absolutely helpless and dependent on them. That endorphin circuitry then requires the good attachments of the parents to develop. If those attachments are troubled or the child is abused, those endorphin circuits won’t develop well and that person will then want that opium or that morphine-like substance from some external source. There you have a heroin addict.

You were talking about that you could trace almost any illness back to attachment. How attachment affects the brain and causes the brain to develop differently. Give us more information about that.

[bctt tweet=”Nobody chooses to be an addict.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]To return to addiction, I mentioned how the body’s endorphin or internal morphine-like opiate system which is essential for pain relief, for pleasure and reward and for love and connection. That system develops or doesn’t in relation to the environment. What’s needed for its development is healthy, attuned, non-stressed parenting support. If you look at another circuit involved in addictions and also in ADD is the dopamine circuitry. Dopamine is another brain chemical which is essential for motivation and attention. If the dopamine circuits are not flowing properly, then the person would be listless, unmotivated and difficult to pay attention. Dopamine flows whenever we’re excited, vibrant, curious, exploring a novel object, seeking food or seeking a sexual partner. The dopamine circuitry of motivation is the main circuitry that’s triggered in all addiction, whether it’s gambling or whether it’s heroin. The dopamine circuitry requires the presence of non-stressed attuned parent and caregivers. If you take the infant monkeys and you measure their dopamine levels and you find them to be normal. Then you separate them from their mothers, within a week or so their dopamine levels will have fallen. The dopamine levels in the infant depend very much on the attention and presence of the parents. Children who are brought up in homes that are highly stressed, but the parents are distracted or depressed or worse where the parents are abusive, their dopamine circuits won’t work properly. When they do cocaine and crystal meth which are stimulants that elevate dopamine levels, they feel normal for the first time in their life. Then they’re hooked.

It’s a myth that drugs in themselves are addictive. It’s obvious that they’re not because most people who try most drugs never become addicted. Most people would try alcohol and never become alcoholics. Most people who eat, don’t develop an eating problem. You can’t say that the cause of the eating problem is the food or the alcoholism is the alcohol. What you need for the disease of addiction to develop are both an addictive or potentially addictive substance and behavior which could be almost anything in the whole world and the susceptible individual. Susceptible individuals are those whose childhoods were difficult that their brain circuit didn’t develop optimally. Most people you can give them morphine all you want for chronic pain or acute pain and they will not be hooked into morphine. When the pain is gone, they get off the morphine. Some people whose early life was difficult and therefore they’re predisposed, they’re the ones who you give morphine to and they feel normal for the first time. whether it’s impulsive shopping, impulsive behavior or drug use. If you do brain scans on drug addicts, the commonest brain finding on the scan is that the part of the brain that regulates impulses doesn’t function. That’s the orbital frontal cortex, typically in the right side. That too needs the same environmental input because it’s no longer controversial, although not yet taught in the medical schools that the brain develops an interaction with the environment.

As Dr. Daniel Siegel who’s a well-known psychiatrist and brain researcher at UCLA has said, “Human connections make neuronal connections.” In other words, human connections create the nerve connections in the brain. Where the human connections are troubled, so will the brain connections be. It also explains why we see many more children diagnosed with all kinds of disorders, which is a problem of impulse control. Significantly with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorders, depression, anxiety and bipolar. The parenting environment in North America and industrial society, in general, has become more and more stressed. It’s not that parents have become less loving. It’s that they’re more stressed. The community, the neighborhood, the clan and the tribe that used to support the parenting task have been eroded. The parents are left on their own more. Most parents don’t even see their kids most of the day. This is why more kids are being diagnosed because the conditions for a healthy brain development are less and less available, despite all the loving that the parents have.

That’s concerning from a number of points of view because it seems that’s going to be difficult to change how much support parents have in parenting. It doesn’t seem like our communities are the same as they were many years ago. We don’t have grandparents who live next to their children and grandchildren as much. It seems to me that there are more and more children who are being abused or mistreated or neglected. Maybe it’s my skewed population I see of patients with addictions and eating disorders. Do you think that’s true?

Hold On to Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers

The numbers are certainly huge and the more stressed people are, the more likely they are to abuse their kids. It’s how it is because they lose impulse control themselves. They get aggressive, they get upset. They take it on whoever is around which is their kid. The other consequence of all that is in the absence of working adult attachments, kids then form attachments to one another. You have this increasing and unordered influence of the peer group on child development. For the first time in history, you have immature creatures heavily influencing each other’s development. There are going to be disastrous consequences for maturation and learning and development when it comes to addiction. That information is in my book, Hold On to Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers. From the perspective of addiction, the commonest context we’re being introduced to addictive substances or addictive behavior is the peer group. The more that parents lose their influence, even non-abusive, well-intentioned parents, the more they lose their influence because of their stresses in their lives and their relative absence in a child’s life. The more the child falls under the influence of a peer group, the greater the risk of being introduced to addictive behaviors.

How does the fetal environment in the womb affect addiction risk because you write about that in your book?

The studies are beyond controversy. As Dr. Robert Sapolsky at Stanford has said that, “We are affected by the environment as soon as we have an environment.” We have an environment as soon as we’re implanted in the womb. We know that mothers, for example, who are abused during pregnancy, will have higher levels of the hormone cortisol in their placenta at birth. The cortisol has a significant effect on the child’s development in utero. Their infants are more likely years later to have developmental problems, which predispose to addiction. We know that we can stress pregnant animals in the laboratory and their offspring will be more likely to use cocaine and alcohol when they become adults. Much information has come along to show the negative impact of maternal stress. If you look at this as a social issue, it’s not just an individual issue. The more you stress people, the less support there is for pregnant women. The less community there is, the more people are forced to economic uncertainty. If a woman is in a troubled or abusive relationship, that is all going to have an inevitable impact on a child’s development.

I’d like to look at some of the populations that have severe addictive issues. This is, for example, the native populations like Native Americans and other native populations. There was a documentary that Lisa Ling did on the Native Americans and their high rates of alcoholism.

[bctt tweet=”The problem is that addiction is designed to solve the problem of emotional distress and pain.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]In Canada, it’s the same thing. About the Canadian native, we don’t call them Canadians. They’re called First Nations Peoples, the same population. In the Vancouver area where I worked, 30% of my clients were First Nations Aboriginal origin where they only make up about 2% to 3% of the Canadian population. If you look at the prison population in Canada, in many federal jails, 40% to 50% of the inmates are native, whereas they only make up a small percentage of the population. The suicide rate, the addiction rate, the alcoholism rate and the autoimmune disease rate are very high in First Nations communities. Historically, that wasn’t the case. There was even alcohol in some areas of what is now New Mexico, for example, before the coming of Caucasians but there was no alcoholism. The alcoholism is a response to being traumatized. The society was traumatized by what amounted to the mass murder that was practiced upon them, particularly in the United States. By the loss of their lands and livelihood that occurred in both their countries. By the many ways in which they were unjustly dealt with. By the sexual exploitation of their women. Native Americans in the North, those females have a much higher risk of being raped than a white woman, most of those by non-Native men.

There is a lot of sexual abuse too in the native communities. All that began in Canada at least in their residential schools where native children were forcibly taken away from their parents. The community was forcibly destroyed. At age three, four or five, these kids were taken away from their parents. Forced to go to these residential schools where they were beaten up for speaking their own language. An alien culture was shoved down their throats and the alien religion was forced upon them. Their own ways were invalidated, declared inferior and forbidden even. On top of that, they were sexually abused for generations. Under those conditions, people become traumatized. Unfortunately, what happens is that we pass our trauma onto every generation, especially when we no longer learned how to parent because we were taken away from our parents.

It seems like a very complex, almost a public health issue. In the many years you’ve worked in this field, have you seen any changes that give you hope that this might be different?

I see both progress and real resistance to progress at the same time. In Vancouver, we’ve established what North America’s only supervised injection site. People come here with their illegal drugs they get to inject and they won’t be arrested. They do so under nursing supervision with clean needles, sterile water, alcohol swabs. They don’t get infected quite nearly so much and they don’t pass infections onto one another like HIV and hepatitis C. If they overdose, they’re resuscitated. That’s a huge step forward in reducing the harmful addictions. A lot of people have trouble with it. The federal government even tried to shut it down. They were prevented from doing so by a vote of the Supreme Court of Canada. That’s progress as far as I’m concerned about working with these people in a compassionate and understanding fashion. At the same time, you have the continuing war on drugs. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk was a professor at Boston University and a world expert on trauma. He says that 100% of the inmates of the federal institutions, of the criminal justice system in the States, began life as abused or traumatized children. What we end up doing is we take children. We try and rescue kids if we can from abuse. In this society we try to do that, the police try to do that. Authorities try to do that, but if we fail to do so and the trauma then is visited upon them. As adults then or teenagers they turn to drugs to soothe their pain and then we make them a social enemy. We jail them and we treat them terribly in jails.

It almost sounds in many ways we’re back in the Dark Ages in this area. That progress has been made in some areas, but when you describe it that way it feels like we’re primitive in our approaches to addiction.

Mind-Body Unity: Addictions are located in a continuum that one sees through our society.

We are terribly backward. We ignore science. The brain science I’ve been talking about, the developmental science, the evidence of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Studies. We also ignore what we’ve learned in spiritual traditions whether Buddhist or Christian throughout the ages. That if you want people to transform, you have to treat them compassionately and with love. That’s essentially the teaching of Buddha and Jesus. Not to mention other great spiritual teachers. You don’t help people transform by further ostracizing and punishing them, you do it by giving them lots of compassion and understanding. Acceptance for who they are and then you can see the transformation happening inside them. We ignore all the evidence and we ignore human experience and ignore our own hearts. It’s a very heartless approach that as a society we visit on the drug addict. That reflects the inner recognition that many of us have those tendencies and we don’t want to face that. We’d rather cast out the devil by focusing our disapproval on a clearly identified drug addict.

I wondered how you were personally affected by the people you worked with.

I saw myself in them. I didn’t see a major difference humanly in terms of dysfunction, except that I’d been luckier in my life. I had certain stresses and traumas in my childhood, but nothing like what they had experienced. You can’t help but be moved by what happens to people. In this field, people die. People have overdoses, HIV and that has an effect. You miss people, you lose people and you mourn them. I also like my clients. They are interesting people, often creative and sensitive. Underneath that hardened demeanor, there is often tremendous vulnerability. Once they begin to trust you, their own vulnerability becomes apparent. Sometimes I would find myself judgmental of them, despite what I know. Those judgments arise and interestingly enough or not so surprising to me, it’s integrity in my own life as I was indulging in one of my shopping sprees, for example. That’s when I’d be more judgmental of my clients. That’s when I have the least tolerance for what I saw as their weakness or their refusal to give up their habits. It is a complex relationship. I learned a lot from them as well. I became a more compassionate human being with a deeper understanding of human possibility and human suffering.

I want to make sure that you know how to find out more information about him, go to his website www.DrGaborMate.com. You can hear past lectures of his. You can see his schedule of upcoming events and find out more about his previous books. Dr. Maté, we talked about what it takes to heal addictions. I want to take a little turn, deviate and talk a little bit about childhood ADHD because there are many children who are being diagnosed with this and put on all of these medications. In some cases, it breaks my heart to see what happens to them when they’re treated this way. Can you tell us a little bit about your philosophy in that and approach?

The medical profession tends to look upon the condition as a genetically transmitted disease. If that were the case, we wouldn’t be seeing all these increases because genes don’t change in a population in a short period of time. Not even over hundreds of years. There are three million kids on stimulants in the United States at last count. In Canada, the numbers of being diagnosed and treated keep going up as well. If we understand that this is not a genetic disease even though I have it and a couple of my kids have been diagnosed, it’s not a genetic disease. What happens is that the child’s brain develops and interacts with the environment. The circuits of attention and impulse regulation which are impaired in ADHD and the dopamine circuits. When we give people Dexedrine or Ritalin or any of these stimulant drugs, what we’re striving to do is to elevate dopamine levels in their brain. Those circuits don’t develop when the parents are stressed or distracted. The more there’s social stress from parents, the more there is a parental distraction, lack of ability of the parent to be present emotionally with the child because of their own problems, stresses and lack of support, the more child developmental brain issues we’re going to see. It’s not a genetic disease though and because the human brain can develop new circuits even later on in life, especially throughout childhood given the right circumstances. The question we have to ask is not how do we fix the symptom with the drug, with the medication, but how do we help this child develop? If you understand that the child’s brain can develop even later, then the question we’ll be asking is what kind of environment do we have to create in our homes?

[bctt tweet=”The addict doesn’t know how to say no.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]What kind of environment to we have to create schools, kindergartens and wherever children are looked after to help promote their brain development? That means whether or not we use medications. We recognize that medications are not the answer. Medications at the very most help you with symptoms and that may sometimes be necessary, but they do nothing to promote development. It’s the child’s environment that we have to look at, how we see the child. These kids, it’s parallel to drug addicts because these kids are either medicated or we try and control their behaviors by means of punishments. We don’t realize that the child is not deliberately behaving in certain ways and that the impulsive behaviors reflect a lack of brain development. The question we have to ask ourselves is what conditions does a child need for healthy brain development? We will be punishing or criticizing the child. We would be understanding the source of the behaviors. We would be promoting an environment that can support healthy behaviors and encourage development. That’s possible with that understanding. Most of that time, the child is diagnosed, all that happens is they got a prescription and that’s the end of the treatment. That’s a subject of my book. The book is entitled Scattered: How Attention Deficit Disorder Originates and What You Can Do About It. That’s the American title of it. That’s a short outline of what I say in that book. ADD becomes a major risk factor for addiction later on too unless you handle it well.

I had an experience with my youngest son where four of his friends were diagnosed with either behavior problems or ADHD. One who was the most severe was finally kicked out of the school system because he was sent to a smaller school where there was 5:1 or 8:1 student to teacher ratio and his whole life changed. It wasn’t about the medication, it was about the environment.

I can trace my own ideas to get back to the fact that I was a stressed Jewish infant in Budapest, Hungary in 1944 under Nazi occupation and all the traumas that my parents endured. All the anxiety, depression and terror that my mother went through that she was looking after me. In a situation like that, the scattering of attention becomes a defensive technique and part of the child. When the stress is too much and the child can’t get away from it, how does he deal with it? By splitting his attention so he’s not aware of it. It’s a God-given or nature-given defensive technique.

You said you were not diagnosed until 52.

I wasn’t because I’m not the most severe case. There are different severities of it.

How do you make changes in your life to help heal the ADHD?

Mind-Body Unity: You know that progress has been made in some areas, but it feels like we’re just really primitive in our approaches to addiction.

Meditation is important for me. I haven’t done this very successfully, but not taking on too much stress in my life. Working on my emotional issues and I’ve been very much affected by that early childhood experience in terms of my emotional behaviors. Working on my relationships, healthy eating and regular exercise, all that stuff is important. In the case of my kids, they grew up in a home where the father was a workaholic, ADD-driven physician and the mother was stressed as a result. Their brains are affected by their environment. We do pass it on generationally, but we don’t do it genetically.

Have you been able to help them to change their environment as you’ve learned about this?

As I learned about it the parenting environment in our home did get better. That made a huge difference for them. Now they’re adults and they have to take on their own healing, I can support them as best I can. Once you’re an adult, you need to take it on yourself.

Let’s go back a little bit to the patients you worked with addictions and many of them you describe in your book, In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts. You described that they also had a pretty severe mental illness. Is that all still a result of the same ideology? How did that affect your treatment?

If you look at the Adverse Childhood Experiences studies you see that the risk of depression, anxiety and psychosis that they all grew up with childhood adversity and ADHD. Probably 20% of my clients would have had ADHD unrecognized and untreated. You have to take that into account. To the person with ADHD when they do crystal meth, it’s like they self-treating, they’re self-medicating. Crystal meth is a stimulant like Dexedrine and Ritalin is. It’s more dangerous and it has a much greater effect, but nevertheless, it gives them that dopamine surge that they’re looking for. You look at addictions from that point of view. You realize that many addictive behaviors or the use of substances are desperate attempts on the part of the individual to regulate the underlying mental health conditions. People will use alcohol to treat their depression, their social anxiety or their ADHD. In one study, 40% of male alcoholics have shown to have ADHD. People will use cocaine as an antidepressant because cocaine, like Prozac, elevates serotonin levels in the brain. People use opiates to self-medicate PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

As we know, large numbers of the veterans who come back from Iraq and Afghanistan suffering from PTSD will gravitate towards opiate use. We have to recognize these underlying conditions that people are self-treating. I’m not advocating that they should self-treat that way because they lead to more problems. In the short-term, it’s their attempt to solve a problem in their lives. We have to look at these underlying and accompanying mental health conditions and treat them. It’s also true that some of the drugs can further exacerbate or cause mental health issues. People who are heavily into cocaine or crystal meth, they can develop psychosis. Even some children or youth who are genetically predisposed in this case, if they do cannabis that can trigger psychosis for them. In most cases, you have at least a double problem of both an addiction issue and a mental health issue that either preceded or followed upon the use of drugs.

[bctt tweet=”The more stressed people are the ones more likely to abuse their kids.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]How have your views been accepted in the addiction field or in the medical world system?

The success of the book indicates that certainly most of the public there’s a lot of appreciation for what I’m saying because it drives people’s experience. I do get invitations to speak to medical groups. I spoke at the California Society of Addiction Medicine Conference in San Francisco. What I had to say was well-received and many physicians who read the book expressed real appreciation for it. I wouldn’t say that on the official and global level these views are much accepted or even taken into account. That’s how it is and I expect that to improve with time. What I do know is I get a lot of invitations to speak to addiction workers, non-medical health personnel and I get lots of people with addictions that write to me and tell me that the book changed their lives. I have difficulty taking credit for that.

It’s very gratifying I would think.

It is and people who find themselves mirrored or understood by that book that will certainly help. In terms of the profession, there’s some acceptance and interest. That’s gratifying. It’s a conservative profession which is slow to change. Even the Adverse Childhood Experiences studies, although they’ve been widely reported and nobody’s ever refuted or even questioned them much, they’re not incorporated into medical practice. That’s the material and brain development, it’s not controversial and it’s state of the art brain science. It’s not yet taught in any medical school that I know about.

What is your vision of what it would take to heal people with addictions?

We have to understand two things. One is that the problems that led to the addiction are lifelong issues. The lack of self-esteem, the shame that the abused child has because they all believe it’s their own fault or that they deserved it somehow. The impulse control problems because of inadequate brain development. The poor sense of relationship, the distrust of authority figures and the generally negative take on the world. They can’t help, but this is ingrained in them in childhood. We have to deal with all the stuff as you can have somebody overcome addiction. Number one, the mental health issues. The drug use itself changes the brain in a negative way. After a period of drug use whether it’s alcohol, heroin or cocaine, you see certain negative brain changes on brain scans. That means that healing is not going to be an overnight affair. Putting someone into detox, helping them clean up from the drug and then shoving them back into the street does nothing for them. Inevitably, they’re going to fall back into drug use. The treatment in the brain changes that addiction causes themselves takes a long time to be reversed, during which time people need compassionate care, nutrition, patience, counseling, no judgment, things that we don’t provide for addicts.

Personally, this has been a wonderful experience of talking with you. I want to thank you for being on the show and sharing this important knowledge and understanding of addictions.

It’s a pleasure to speak with you as well and thanks for the interest.

I want to thank everyone and until next time, I wish you good health and vitality.

Important Links:

- Dr. Gabor Maté

- In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction

- When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection

- Hold On to Your Kids: Why Parents Need to Matter More Than Peers

- Scattered: How Attention Deficit Disorder Originates and What You Can Do About It

- California Society of Addiction Medicine Conference

- www.DrGaborMate.com

About Dr. Gabor Maté

A renowned speaker, and bestselling author, Dr. Gabor Maté is highly sought after for his expertise on a range of topics including addiction, stress and childhood development. Rather than offering quick-fix solutions to these complex issues, Dr. Maté weaves together scientific research, case histories, and his own insights and experience to present a broad perspective that enlightens and empowers people to promote their own healing and that of those around them.

A renowned speaker, and bestselling author, Dr. Gabor Maté is highly sought after for his expertise on a range of topics including addiction, stress and childhood development. Rather than offering quick-fix solutions to these complex issues, Dr. Maté weaves together scientific research, case histories, and his own insights and experience to present a broad perspective that enlightens and empowers people to promote their own healing and that of those around them.

For twelve years Dr. Maté worked in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside with patients challenged by hard-core drug addiction, mental illness and HIV, including at Vancouver’s Supervised Injection Site. With over 20 years of family practice and palliative care experience and extensive knowledge of the latest findings of leading-edge research, Dr. Maté is a sought-after speaker and teacher, regularly addressing health professionals, educators, and lay audiences throughout North America.

As an author, Dr. Maté has written several bestselling books including the award-winning In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction; When the Body Says No: The Cost of Hidden Stress; and Scattered Minds: A New Look at the Origins and Healing of Attention Deficit Disorder, and co-authored Hold on to Your Kids. His works have been published internationally in twenty languages.