—

Listen to the podcast here:

Misdiagnosing ADHD And ADHD Natural Remedies with Dr. Sanford Newmark

My special guest is Dr. Sanford Newmark. We’re going to be talking about how to treat ADHD without drugs. Dr. Newmark is a Clinical Professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of California. He is Head of the Pediatric Integrative Neurodevelopmental Program at the Osher Center for Integrative Medicine specializing in the treatment of autism, ADHD and other developmental or chronic childhood conditions. He graduated from the University of Arizona College of Medicine and did his pediatric residency also at the same place. After practicing general pediatrics in Tucson for twelve years, he completed a fellowship in Integrative Medicine with Dr. Andrew Weil’s program at the University of Arizona. Welcome to the show, Dr. Newmark. Thanks for being here.

I’m delighted to be here. Thank you.

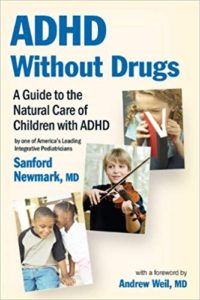

ADHD Without Drugs – A Guide to the Natural Care of Children with ADHD ~ By One of America’s Leading Integrative Pediatricians

You wrote a book called ADHD Without Drugs: A Guide to the Natural Care of Children with ADHD. It’s a wonderful book giving a totally different perspective on ADHD, which is essentially dominated by the use of medications in treating children.

Part of why I wrote the book is I was concerned about the dominance of medications. Although I’m not against using medications in ADHD in certain circumstances, I don’t think that should be where we look first.

It seems to be the case. Is it my imagination or over the past decade have there been an increasing number of children being diagnosed with ADHD?

It’s not your imagination at all. It’s not just the past decade. In 1970, there were 150,000 people using stimulants. In 2003, there were 2.5 million. The number of children diagnosed is around 9% of all children. Almost one in every ten children has received the diagnosis of ADHD, which makes it tied with asthma for the most prevalent disease of childhood.

How can you explain this massive increase?

There are a few possible reasons. One, maybe these children all had ADHD and we never found them. Two, maybe we’ve loosened the definition or we may be misdiagnosing people for a number of reasons. The final thing there may be reasons to think there are more kids who do have ADHD. There’s some truth in all of those. It’s a combination.

Is our incidence of ADHD in children the same as other developed countries across the world, like England or France or Germany?

If you look at the number of kids who are diagnosed and treated, we’re by far and away the most. Ours is way more. If you do studies and you go to other countries and you ask whether kids fulfill their criteria for ADHD, other studies show that it’s similar. The question is how the culture looks at these symptoms and what they decide to do about it if anything.

What you’re saying is they may see the same picture in children, but they don’t necessarily label them as having ADHD or treat them in that way?

Exactly. The rate of Ritalin use or other stimulants in the United States is way higher than anywhere else.

What is research showing us about the essential causes behind ADHD? In your book, you write quite a lot about some of the studies of brain scans that are showing differences in the brains of children with ADHD and also differences in the feel-good chemicals that our brains make. Can you say a little bit about that?

[bctt tweet=”To what degree a child has ADHD is also dependent on environmental influences, not just genetics.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]There have been a lot of brain scans and other investigations to try and figure out what’s going on with ADHD. Although the studies vary in what they find, the thing that seems to be the most prominent is that the frontal lobe of the brain seems to be less well-developed and seems to work less well. That’s the part of the brain that essentially is responsible for what we call executive function. That’s the part of their brain that’s putting the break on things. That’s the big decider of how we react to things. The frontal lobe is responsible for that. When something happens and we react, usually the frontal lobe is there to put a brake on and say, “How should we react? Should we react?” That is relatively undeveloped in three-year-olds. Nobody’s frontal lobe is well-developed. As we get older, that frontal lobe develops more and more. Children with ADHD, it develops more slowly.

It could explain why children with ADHD have poor impulse control.

Absolutely, that’s why they have poor impulse control and why they’re distractible and even why they’re hyperactive sometimes. A lot of children who are labeled with ADHD aren’t hyperactive. There are also changes in the circuits of the brain, how that frontal lobe is sending messages to various other parts of their brain. That’s the most basic thing.

Is that a permanent difference or is it a developmental delay?

Some studies have shown that the kids’ frontal lobe catches up. Other studies show that even adults with ADHD may have similar changes.

Is it possible there’s a segment of people who genetically are hardwired that way and then there’s another segment who may be slower in developing in that way and may catch up later?

ADHD: A trial of Ritalin is not an adequate substitute for a thorough diagnostic evaluation.

That’s exactly right. We don’t know what makes people catch up or not or what makes one subset different than another. Maybe, in the end, it’ll turn out to be genetic but the environment plays a huge role. That’s another thing about ADHD when you ask about what causes it. We know it runs it strongly in families. Most of the time when I see a child with ADHD, either the mom or dad or an uncle has similar symptoms even if they weren’t diagnosed. There’s a strong genetic tendency. How that’s expressed and to what degree the child has ADHD seems to be dependent on environmental influences so it’s not just genetics.

When you say environmental influences, what kinds of things in the environment can predispose or trigger ADHD?

Everything from the time the child is conceived on we believe that for instance, toxins in the pre and postnatal environment can do it. As an example of that, children who are exposed to prenatal tobacco use by their moms had a two-and-a-half times higher risk of having ADHD. It’s four times higher with children with high blood levels. It’s higher with kids who are exposed to certain pollutants.

Toxins even before a child is born can influence this. After birth, what are some of the environmental influences?

Some things like toxins and pesticides. One study showed that children who had higher levels of pesticides in their urine, meaning that they are ongoing taking in pesticides, had twice the odds of having ADHD as kids who had the lower levels of pesticides in the urine. Ongoing exposure to toxins increases your chance of having ADHD. Probably it’s going to turn out to be a great variety of toxins, but we don’t know. One study that’s very scary showed that they took the umbilical cord blood of ten newborns scattered around the country. This is what they’re bathed in before they even take a breath, the first nine months of life. They detected an average of 200 industrial chemicals and pollutants. Out of those, 217 are known to be toxic to their brain and nervous system at some level. Some of these were at extremely low levels, but when you combine them all, nobody has any idea how much it takes to affect the developing brain.

Assuming we have more exposure to these toxins now than many years ago.

[bctt tweet=”Children with ADHD especially need good nutrition.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]The number of chemicals has increased dramatically except for lead. We’ve gotten to decrease lead in the environment.

I like a quote in your book where you say, “A trial of Ritalin is not an adequate substitute for a thorough diagnostic evaluation.” Why do you say this?

Ritalin can cover up a lot of other issues and problems. In fact, anybody who takes Ritalin is going to concentrate better and be less distracted. This is the big secret is it works on everybody. The fact that a child who is given Ritalin may concentrate better or be less distractible doesn’t mean that he has ADHD.

It seems that many physicians are using that as a way of determining whether someone really does have ADHD.

That’s exactly right and I’m against that type of approach.

We were talking a little bit about environmental factors that can influence or trigger the development of ADHD. You had one more which you wanted to mention.

ADHD: Sometimes, there isn’t a reaction to the food until it’s reintroduced.

Television is another factor that research has shown can increase the risk of having ADHD. At first, few studies showed a correlation between television watching and ADHD, but nobody was sure if that was because children with ADHD watch more television or television was causing people to be more ADHD-ish. A study confirmed that it looks like television and by implication video games and other electronic media can increase the risk of having ADHD or have ADHD being worse. That’s another significant environmental factor.

Is there a break-off point where TV watching is too much? Is there any safe level of TV watching or video game playing?

There probably is but we don’t know it. I advise people to limit screen time to an hour, half an hour on school days and maybe little more on weekends. Any more than that is too much, but we don’t have the research to pick a number.

That seems to be a real tough one for parents to enforce because in our culture it’s natural for kids to nowadays anyway to be sitting in front of the TV all day.

It is. The length of the camera shot and otherwise how long the camera stays still on one thing has dramatically decreased over the last decades. Where you used to be watching television and you’d be seeing one scene, think Mister Rogers would be talking to Captain Kangaroo. You move to Sesame Street, then you move to the MTV video style and now kids are getting flashing images changing every second or two or three. It’s easy to see how that would make them have a difficult time focusing or concentrating for longer periods of time.

They go from watching TV to going into a classroom where things don’t move fast at all.

[bctt tweet=”Our culture, by way of television, has lost touch of good nutrition.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]I feel for teachers trying to keep kids’ attention these days.

How do you go about diagnosing a child with ADHD? I have many of my patients who are parents and they come back and say, “The teacher told me that my kid has ADHD because he won’t sit still in class or he’s talking too much,” or some other reason. What should parents know about what it takes to diagnose ADHD?

The first thing they should know is that this is a process that takes time and it takes somebody who knows the field and is dedicated to it. This could be a pediatrician or family practice doctor or a developmental pediatrician. Sometimes a psychologist is important, but it has to be somebody who is interested and knows that the field and will take enough time. My evaluation for ADHD usually takes two to two and a half hours, which in my practice is split over two sessions because I need to talk to the parents in depth. I’m going to get a complete medical history, a complete developmental history. When the child is old enough, especially in a school age child, I talk to the child alone. I talk to the parents without the child there. Standardized questionnaires are an important part of it. There are these checklists that parents and teachers can fill out. It’s a part of the exam, but not the whole thing. I like to speak to teachers or anybody who’s done evaluations or at least if they’ve had a psychological evaluation, I read that and I take a look at it. All of that needs to be done before I can make a good diagnosis. On the other hand, the way it often works is a teacher or somebody else, sometimes it’s the parents will say, “I think he has ADHD.” Parents will go into their pediatrician and they’ll talk for ten minutes. The pediatrician will give them a couple of forms to fill out and then they’ll come back with the forms. Teacher fills out one, parents fill out one and he says, “These forms are positive, so he has ADHD,” and they’ll try him on Ritalin. That’s often the whole workup. It’s not just me who says that’s inadequate, even the American Academy of Pediatrics says that’s inadequate. They say it should be an hour or two of evaluations. In the real world, that often doesn’t happen.

I know the teachers are bleak but there also seems to be a desire to make the teacher’s life easier. If we can get this kid to calm down, then the school will be easier for them.

That happens in a lot of cases. I have great respect for teachers and I know what they’re dealing with these days, especially with the No Child Left Behind and teaching to test them. Many teachers are good about not suggesting the diagnosis too early, but some teachers do immediately go there because it makes their life a lot easier. They think it will be better for the child. What that brief diagnosis can miss, that is the problem. When you’re doing this in ten or twenty minutes, you may miss a child with learning disabilities and learning disabilities like dyslexia are different from ADHD. If you just treat the ADHD, you miss the problem. Kids who are anxious or even depressed can look like they have ADHD, a bored gifted child. I’ve had kids in my practice that were flat-out bored and they started fooling around and not paying attention. They didn’t bother to do the work because it was too easy. You get them in the right classroom and suddenly the ADHD symptoms are gone.

That’s important because not every child belongs to a large public school setting. Some children belong in art school or a more creative setting. That’s important for people to know that it should take time to diagnose. You have quite a lot of excellent information about nutrition in your book. There’s a story there about a school that did an experiment and this school was in Wisconsin. In your book, you say, “Good nutrition is especially important for children with ADHD.” Maybe you can tell us a little bit about that experiment that was done or the research study.

ADHD: Having your child remain healthy is more important than worrying about whether they’re eating the same cereal as their friends.

There’s a place called Appleton Central High School, which was Central Alternative Charter High School, which was in Wisconsin. This was the place for kids who are having a hard time or described as disruptive, truant and had psychological and emotional problems. They came from dysfunctional home environments. It’s that school, they had big issues. What happened is the school decided to take out all the vending machines that had any junk food in it, the soda, the chips, all that. They got a company called Natural Ovens to begin a healthful meal program for breakfast and lunch. Fortunately, these kids all ate breakfast there so we were able to change their breakfast and lunch. With breakfast and lunch, they served this good healthful food and they got rid of the junk food. The change in the school and the students was remarkable. I’ll quote what the principal says, “I can say without hesitation that it’s changed my job as a principal. Since we’ve started this program, I have zero weapons on campus, zero expulsions from the school, zero premature death through suicide and zero drugs or alcohol on campus. These are major statistics.” You can imagine what school this was.

If they were tracking suicides and deaths and you skipped over that, what you’re saying is changing their diet only two meals a day dropped their rates of death and suicide.

Other comments from teachers, “Students’ disruptive behavior and health complaints diminished substantially. They seem better able to concentrate. They’re more attentive.” There’s a wonderful video if you Google Appleton Central High School, you will find it online. It’s an old the videotape and it has lots of comments from the students and faculty and it’s quite remarkable. When you can make that change in kids who had those difficulties, it tells you a lot.

It certainly does. Can you tell us a little bit about what nutritional changes kids with ADHD tend to respond to?

I’m going to divide it into two things. One is basic nutrition and the other is food sensitivities or allergies. Those are two different approaches. Basic nutrition refers to how well kids eat their breakfast and lunch. It’s not giving them pop tarts or white flour pancakes and syrup for breakfast, but giving good, low-glycemic, unprocessed carbohydrates with some protein and fat for breakfast and the same for lunch.

It’s getting them off to a good start with basic good nutrition which seems we’ve lost touch within our culture. Everything is sugary for kids and all of the TV ads for foods for kids or foods are very highly processed. We don’t see commercials on TV for kids to eat their vegetables. Nutrition is underrated as a therapy in this area. That’s the generally good food and then there are a couple of other things that people need to know about nutrition.

[bctt tweet=”It’s a good thing to be able to treat children with ADHD just by managing their diet.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]What it turns out is that many children with ADHD have food sensitivities. That means that certain foods that they’re eating can significantly hurt their behavior and cause ADHD symptoms. Most often these aren’t true food allergies. If you went to an allergist and got to a blood or skin tests for allergies, they may not be positive, that’s why I use the word sensitivities. These can be common foods that are necessarily not healthy. Foods like dairy or wheat or corn or soy can trigger children to behave in an ADHD manner, to be impulsive, to be hyperactive and to have difficulty concentrating. When these three foods are removed from the diet, you can see significant changes. This has been shown in a number of research studies. This is not new or an alternative information. As an example, in 2017 a study was published in The Lancet, which is maybe the world’s most prestigious medical journal. They took 100 kids and gave 50 of them a restricted diet where they weren’t eating any milk or wheat or dairy and a few other things and had 50 other kids who were controls. The children who went on this restricted diet, 70% of them had significant improvements in their ADHD. This is not the first study to show this, but it never makes the popular medical literature because nobody stands to make any money out of this.

If a parent is worried about that, do they need to get a blood test for this? What do you recommend?

I don’t always recommend a blood test unless some other symptoms make me think that the child has true allergies, like asthma or chronic allergies or hives. I don’t even necessarily do a blood test for that, although I do a blood test for other things in ADHD. What I do is I have them do what I call an elimination diet, where they eliminate a number of these foods for a period of about three weeks and they see what happens to the child. After three weeks on this elimination diet, which I go over with them carefully and we go over the nutritional aspects, if there’s no change, then you’ll say, “This child food doesn’t seem to make a difference.” If there is a big change, if the ADHD symptoms are significantly better, which I see on a regular basis. It’s certainly not every kid with ADHD. Maybe 25% to 40% of them will have some significant improvement.

You noted in your book that sometimes there isn’t a reaction to the food until it’s reintroduced. They may not have that significant improvement. However, when they start back eating the dairy, then their ADHD symptoms may get worse.

You don’t notice the change so much until you add back the food and then you notice it. When that happens, it’s a good thing to be able to treat these children by managing their diet. The other thing about food sensitivities is that kids with ADHD are often sensitive to artificial colors, flavors, and preservatives. There’s been a lot of research showing that they make normal people more hyperactive and ADHD people worse. In fact, in Europe for certain food colorings, there’s a warning label that people have to put on and it says, “This may make your child hyperactive.”

We don’t have that here.

ADHD: Negative attention to a child with ADHD is better than no attention.

We don’t. The FDA reviewed that and they said, “Food colorings can make kids more hyperactive, but we don’t need a label.” It shows how strong, at least the people in Europe, considered this evidence. One simple thing to do is to try and avoid these artificial colors and flavors. A good example is Gatorade. Every Gatorade except the clear one has artificial colors and our kids are drinking this by the ton.

Even yogurt is colored.

Even yogurt, Cheez-Its. People put these artificial flavors and colors into so many things. They’re pretty easily avoided and you can get the same things. You can get little cheese snack things that have natural color instead of artificial color. I often recommend for instance, Trader Joe’s. They often have substitutes and they rarely have artificial colors and flavors in their products.

I’m sure that you, as a pediatrician, hear a lot about parents’ fears that they can’t get their children to eat a healthy diet. There’s a wonderful quote in your book from Ellyn Satter who is a leading feeding therapist and she says to parents, “Your job is to offer your child the food you want to offer at the time you want him or her to eat it. The child’s job is to decide what and how much of it to eat.” What do you do when a parent comes in and says, “I can’t get him to eat vegetables?”

I say, “You’re right. You cannot get them to eat vegetables.” What you can do is not offer other things that you don’t want them to eat.

“My child’s going to starve. Won’t he be hungry?”

[bctt tweet=”Though you may not get children to eat vegetables, what you can do is not offer other things that you don’t want them to eat. ” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]They do say that sometimes then I say, “99.9% of children will eat plenty, even if you take away the foods that they usually like, even if you take away the junk foods. It may take a few days. It may take a week. Their hunger will take over.”

Your children will starve to death.

I still haven’t found that child who starved to death on one of these diets. What I emphasize is when children are young is when parents have the control. This is when they can set the child’s eating habits and doing it by example and what’s available in the house. If there’s no soda in the house, the child won’t drink soda. If there are no junk foods, sweets, the child won’t eat them. I don’t like to be dogmatic. I don’t think children should never have a soda or never have a treat. A certain amount of those is fine. The general thing that children eat like sugar cereals is a good example. Why keep Lucky Charms or Cocoa Puffs in the house? There’s no reason a child should be eating them.

I know some parents feel they’re depriving their children if they don’t allow them to eat these special fun foods and their friends are eating it. “Why can’t I?”

Having your child remain healthy is more important than worrying about whether they’re eating the same cereal as their friends. You can always have one of these things for a treat.

Transforming the Difficult Child: The Nurtured Heart Approach

A treat should be a treat and that’s something that is infrequent, not every day or three times a day.

When you offer your child breakfast, you can offer choices. “You can have this healthful whole grain cereal or you can have a piece of whole wheat bread with peanut butter and a glass of milk or you can have some yogurt and fruit,” and the child can pick. It’s that pancakes with syrup are not on that choice.

We teach our children what to eat from a young age. It’s best to start out as early as possible. We talked about how many children are being put on stimulants such as Ritalin. What’s wrong with that? Why not give children even if they are marginally diagnosed with ADHD? Why not give them Ritalin?

Ritalin and its derivative work in about 70% of the cases. They cause the symptoms you’re trying to treat to get better. There are two reasons. One of them is that there are often significant side effects. These side effects can range from minor to slightly decreased appetite, but they can be more. They can have significantly decreased appetite and weight loss that can impede growth. They can cause headaches, stomachaches, occasionally 1% of the time hallucinations. There are also children who don’t have such obvious side effects. I hear this from parents, a fair amount where, “Yes, he’s doing better but he’s not as joyful or she doesn’t have that spirit that she used to have.” It can decrease this natural, brilliant, happy spirit that kids have. It doesn’t happen all the time, but it does happen. That’s something to watch out for. Even more important, we don’t know what the long-term effects of giving children these psychostimulants for five, ten, fifteen years are going to be on their eventual development. We know it will cause changes in the way their brain develops, that’s without a doubt. You can’t change the neurotransmitters in a child’s brain, which is what these stimulants do on a daily basis for years and years without changing how the brain develops.

We’re doing essentially a large experiment on a huge number of kids by giving them the stimulants. Some of them are getting them very young and yet we don’t have the studies to show us what these long-term benefits are what you’re saying.

It’s a large uncontrolled experiment. The kids who were it’s obvious they desperately need them. There’s a true diagnosis, a truly significant need. You say, “What’s happening to the child is worse than what some possible long-term effects are,” and I understand that. Let’s not jump to treat the kids with mild symptoms. We can work on the nutrition and certain supplements which we haven’t talked about first.

What are some of the alternative therapies that you use in your practice to treat ADHD?

I use a nutritional supplement for that which I don’t think should be called an alternative. Compared to how most doctors operate, I guess it is. What we know is that certain kids with ADHD may be low in iron, zinc, and magnesium. All those minerals have been shown to be important in ADHD symptoms. There have been studies showing that all of those minerals can improve children’s symptoms. Iron was particularly dramatic in one study. Kids who had ADHD had an average iron level of 22 and those without ADHD had an average iron level of about 44. When those kids with the low iron were then treated, their ADHD symptoms improved significantly at the same amount that medication might improve them. These are important things to check iron, magnesium, and zinc. I will supplement those when I need to. There have also been a number of studies about omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, and ADHD. A lot of people know that fish oil is important for good brain function. Most people in our society are deficient in omega-3 fatty acids. I always supplement the kids with ADHD with fish oil. It’s good for their general health and it’s good for their ADHD.

Do you use cod liver oil?

I use fish oil that’s not cod liver oil. You can use cod liver oil. I don’t think they need all that preformed vitamin A that comes in the cod liver oil. Either way, it’s okay.

[bctt tweet=”Ongoing exposure to toxins increases your chance of having ADHD.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]What about herbal remedies for ADHD?

Herbal remedies are a little sparser. There’s one called Pycnogenol that can be quite helpful, which is something that comes from the bark of a European pine tree. There’s an herb called valerian which in combination with lemon balm calms kids down a little. I’ll even use that for kids who are on a medication or having a rebound effect when their medication wears off. It’s calming but doesn’t necessarily help their concentration.

What about some of the behavioral things?

How you behaviorally manage these kids is tremendously important. Many parents end up frustrated, upset, angry with the behavior of their kids with ADHD and it’s no surprise. They end up in a negative interaction pattern with their child. The ADHD child may end up misbehaving to get this attention. The negative attention becomes a big part of how they get their reinforcement. You wouldn’t think they like negative attention, but to them, it’s better than no attention. There’s a wonderful system called the Nurtured Heart Approach. It’s described in a book called Transforming the Difficult Child by Howard Glasser that I love and have had tremendous success within ADHD kids. In this approach, it’s based on the idea that these kids have inordinate needs for attention and almost all the parents I talked to whose kids have ADHD nodded and smile when I say that. When these kids don’t get their needs or attention met positively, they will happily seek out negative attention. That happens a lot with kids with ADHD because people are always going to have negative feedback. They’re always been told to, “Sit still. Be quiet. Why didn’t you finish that? How come you didn’t brush your teeth? Where’s your paper? Get organized.” In this approach, it reverses it where you give the children lots of positive feedback for the good things that they do. What you do is you have good rules and consequences, but you give those without energy. You give those without intensity and emotion and anger and lecturing. The child is not getting your emotional energy for bad things, but for good things.

It should be something as simple as, “Thank you for closing the door.”

You have to start small because they’re not doing that many things right. It can have tremendous effects and often quickly. That’s a big part of the approach. The other part of the approach is to make sure the kid is getting the right school intervention. Many times I hear a history that sounds like, “First grade was great, but then second grade was a complete disaster. Third grade went pretty well, but it’s fourth grade and things are a disaster again.” That’s all about what’s going on at the school, the fit between the teacher and the child. It’s important to make sure the child’s in the right school if you’re lucky enough to have a choice, the right teacher if you’re lucky enough to have the choice and at least the right interventions. Children diagnosed with ADHD have a right to a 504 plan, which are reasonable interventions in the classroom. Some of the interventions are sitting in front of the class. It’s not having to do 30 math problems that are all the same but maybe do ten or fifteen are being graded on them, being given a little extra time for tests and writing the homework down for them. Whatever that particular child needs to help them succeed, it’s important to make sure that those things are happening.

If you are a parent whose child has or has not been diagnosed with ADHD but you’re suspicious or someone has told you that your child has ADHD, what are the steps that you should take to ensure that you get the right diagnosis and the right treatment?

You need to find a medical professional who is experienced in dealing with ADHD. This can be a pediatrician or family practice doctor. It can be a developmental pediatrician, occasionally a neurologist but they don’t like to do that stuff so much. Sometimes even a good psychologist, although psychologists would have to be combined with some type of doctor and work together since psychologists don’t do the medical part. Find somebody like that and make sure you get a good evaluation with learning disability testing if necessary. When the evaluations all are done, then you can decide, “Am I going to do nutritional interventions? Behavioral intervention? What school interventions?” Only the minority of cases need to be treated with medication immediately.

It seems even if they end up on medication, it doesn’t do any harm to start with some of the nutritional therapies or the dietary supplements.

In fact, there are some studies showing that, for instance, zinc even if you’re on medication will decrease the amount of medication you need to use which may make a big difference.

Any pieces of advice to our audience who has children with ADHD? Not everybody can find someone like you and I definitely want to recommend your book called ADHD Without Drugs. It’s well-written and is full of information.

Make sure you get a good evaluation and look at the non-medical, non-pharmaceutical ways of treating first. Always be aware that children with ADHD have many wonderful, good and creative qualities. The goal of life is not to make every kid sit still in school and do the same work as everybody else. Sometimes these children are wonderfully creative and talented.

I assume people can get your book in most bookstores or online?

It’s on Amazon. Some bookstores have it, but I would say probably online is this quickest, easiest way.

I want to thank my guest, Dr. Sanford Newmark, author of the book ADHD Without Drugs. Especially thank you, the reader of the blog. I wish you good health and vitality.

Important Links:

- Dr. Sanford Newmark

- ADHD Without Drugs: A Guide to the Natural Care of Children with ADHD

- Transforming the Difficult Child

About Dr. Sanford Newmark

Prior to joining the Osher Center, Dr. Sanford Newmark founded the Center for Pediatric Integrative Medicine, an integrative medicine consulting practice treating a wide array of pediatric problems. He specializes in the integrative and holistic treatment of children with autism and ADHD, combining conventional medicine with nutrition, behavior management, and various complementary modalities.

Prior to joining the Osher Center, Dr. Sanford Newmark founded the Center for Pediatric Integrative Medicine, an integrative medicine consulting practice treating a wide array of pediatric problems. He specializes in the integrative and holistic treatment of children with autism and ADHD, combining conventional medicine with nutrition, behavior management, and various complementary modalities.

Dr. Newmark lectures widely on both autism and ADHD and has authored three chapters in integrative medicine textbooks. He is the author of the book “ADHD Without Drugs, a Guide to the Natural Care of Children with ADHD.” His online video, “Do 2.5 Million Children Really Need Ritalin? An Integrative Approach to ADHD” has been viewed over 4.5 million times.