Guilt and shame during or after traumatic experiences can make it difficult to recover from the pain of trauma. A reason for that is that unworthiness to feel better because of what a person felt they had done wrong. In this episode, Dr. Carolyn Allard, Associate Professor and Program Director of the PhD Program at the CSPP at Alliant International University, dives deep into a one-of-a-kind method of treating guilt and shame. She and her colleagues have developed the TrIGR approach — Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy — that can be used to help people with PTSD and other forms of posttraumatic disorders related to combat, sexual and interpersonal abuse, childhood abuse and neglect, and other types of trauma. Guilt and shame are only recently being studied as a way of helping people heal from trauma. With TrIGR, you have a well-developed and tested approach to identify causes of guilt and shame and a concerted approach to treatment.

—

Listen to the podcast here:

Treating Guilt And Shame Resulting From Trauma with Dr. Carolyn Allard

Beyond PTSD – How Guilt And Shame Can Keep You Stuck In Traumatic Experiences

My special guest is Carolyn Allard. Let me tell you a little bit about her. She’s an Associate Professor and Program Director of the PhD program at the California School of Professional Psychology at Alliant University. She is also Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego and a research psychologist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, where she served as the Director of Military Sexual Trauma and Interpersonal Trauma Clinic and the Advanced Fellowship in Women’s Health for over ten years. Dr. Allard is a licensed psychologist in the state of California and is board certified in Clinical Psychology. It’s so great to have you and as I mentioned before we got started, I love your book. I want to make sure that we cover it very well. The book’s title is Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy which is a mouthful, but let’s start by talking about why you got involved in researching and writing a book about guilt and trauma.

I am going to introduce you a short form of the therapy, which we called TrIGR. It’s a little less of that mouthful, but thank you for inviting me. I’m thrilled to be here and to be talking to you about TrIGR. It was born out of my work with veterans who have experienced trauma and are dealing with PTSD, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder while I was at the VA. Way back when I started doing my internship there and working with a colleague who also worked with this population, we were working with folks who have experienced domestic violence. We’re noticing the tremendous amount of guilt and shame that that particular population had and that often when we are providing treatments for PTSD, which are effective, we have great effective therapies for PTSD. We were trained on those and we’re implementing those and noticing that for many people, guilt and shame were holding them back from progressing, from benefiting as much as they could from these treatments or as much as we saw other people who didn’t have as much guilt and shame as part of their trauma.

It’s so interesting because I don’t know if you know much about my background, but I work with people with substance use disorders, particularly opiate use disorders. I worked with eating disorders. The majority of the patients I work with as you’ve talked about in your book also have a history of trauma. I’ve noticed the exact same thing and have done a lot of reading. I’m trying to understand this connection. I think your book TrIGR is the best iteration of that. It is very clear and gives you more information about that link and what to do about it. Let’s start by checking out, what is the difference between guilt and shame?

They’re very interrelated. It’s an excellent question. Technically, guilt is the experience of thought and a feeling around having done something that goes against one’s values that somebody feels bad about. Shame is an experience of thinking and feeling that is about more global, it’s an attribution of the self. “I am bad.”

What would be an example of that in some of the people you’ve worked with guilt and shame?

When it comes to trauma, they usually come hand in hand. TrIGR is applicable to both forms and usually, you see both of them. What happens is you initially might feel guilty about something you did or didn’t do that you think may have contributed to the trauma or at least didn’t prevent or didn’t prevent it. It festers and develops into more global shame. “I did something bad, therefore I am bad.”

Not everybody who has experienced trauma feels guilty as you said in your book. Is that correct or feels shame?

[bctt tweet=”Guilt and shame are common features in many of the problems trauma survivors experience including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance use, and suicidality.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]That is correct. Here’s the caveat though, I have not seen one person who I’ve treated for PTSD or either post-traumatic related distress. It comes in all shapes, forms and sizes. Sometimes you’ll be treating somebody with substance abuse and they may not meet full criteria for PTSD, but it’s a post-traumatic reaction. In other words, you have to help them process the trauma to recover from their substance addiction. The caveat I was saying is that in my practice of working with folks who are experiencing some functionally-impairing distress related to trauma, guilt and shame is always present. I use always I have to say very carefully because I know it’s an extreme word and so I intentionally used it there. I have not worked with anyone who has post-traumatic distress, who needs treatment for it who does not have some guilt or shame associated with that.

I think the sentence you stated before that people can’t get well from their substance use disorder until the trauma is treated is very important. In the addiction world and the addiction treatment world, there isn’t a lot of buy-in for that. I speak a lot to addiction conferences and treatment centers. The abstinence model still has a firm hold on treatment and no recognition that the reason people keep recycling back in the treatment and relapsing. Recovery relapse is oftentimes untreated trauma.

The research so far is supporting what you just said in that. It lends support to disorder model where you want to treat both the substance abuse and the trauma or whatever the source of the distresses that leads somebody to self-medicate.

It could be depression or an eating disorder. Your anxiety can also show up that way, right?

PTSD and post-traumatic distress is usually comorbid with other things and most commonly is depression, but it comes very frequently with a substance disorder. The research is showing that if you don’t treat the PTSD, there’s going to be more relapse, you’re not going to be effectively treating the addiction. It’s going to take just cultural shift in the larger population of substance use disorder providers.

Do you think that guilt and shame served a purpose in someone’s mind, someone who had a traumatic experience? Is there a purpose that it serves?

We talked about that in the book as well in terms of the function of the guilt and the shame. It’s helpful to help identify what that might be for an individual. What we see very often is that it serves the function of a couple of different things that we see pretty often. One is if I put the blame on me. Let’s say something bad happened, I experienced a trauma and I put the blame on me. I tell myself, “I did something wrong, I should have done something,” then I can retain the sense of control over what happens to me. Therefore, if I can figure out what it is that I did wrong, I can prevent it from happening again. That gives me a tremendous sense of relief and comfort even though the guilt is very aversive.

Treating Guilt And Shame: People hold on to feeling bad in some way to memorialize somebody they may have lost or who was negatively affected by the trauma.

The guilt is a problem but it also serves a purpose.

Exactly, which is why we think it’s so common. It gives us a sense of control. The other function that we see that it serves often is people hold onto feeling bad in some way or other as a way to memorialize somebody they may have lost or somebody that was negatively affected by the trauma. We see this often in combat veterans who’ve lost comrades, colleagues. They feel like it’s their burden or their cross to bear.

They may feel disloyal I would think if they’re feeling guilty.

We worked through that and we have some tips in the book on how to do that.

You talk a little bit in the book about how sexual abuse can show up somewhat differently than other traumas. How does that relate to shame and guilt on someone who’s been sexually abused?

It doesn’t in lots of complex ways as many things do, but I will talk about a couple of ways that we see it very commonly. One is that sex in our society is often just a source of shame. It’s not something we talk about openly and freely. We certainly have different guidelines of what’s allowed for men and for women to talk about and not talk about and feel about sex. In and of itself, the topic of sex can produce feelings of guilt and shame. That’s sort of an added layer. The other piece is that it’s an interpersonal trauma so that somebody is traumatizing you, is perpetrating this trauma. Often it’s somebody that you know, somebody that you’re close to, somebody you depended on and that even adds another layer. In that we’re social beings, we’re dependent on other people.

We’re dependent on having status in whatever social group written. Often we need to maintain attachment to others. In the case of child sexual abuse, for example, it’s like epitomizes what I’m talking about here, which is what we call betrayal trauma where you’re dependent on somebody else, you’re a child, you’re dependent on your caregiver via parent or another adult for your survival. Normally, if somebody abuses me socially or misuses my trust that usually triggers this confrontation withdrawal response. That’s like my survival response and a social betrayal situation. If I’m dependent on that person, then I need to shut that off to maintain attachment.

[bctt tweet=”Shame is an experience of thinking and feeling that is more about global and an attribution of the self.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]In other words, the natural response would normally be to avoid that person who has hurt you or your child. That’s your caregiver. You cannot do that.

You have to maintain attachment that has to supersede any other adaptive response. Your number one job when you’re dependent on somebody is to maintain attachment. That compels you to approach, not confront or withdraw. What we’re finding in those situations, one of the ways that we can maintain attachment with somebody who abuses us if we’re dependent on them is to put the blame on ourselves. If it’s not your fault, it’s my fault. I can maintain attachment to you.

I can still be your daughter or your son because it’s my fault. I did something wrong.

I did something wrong or there’s something so wrong about me that you have to treat me this way.

It makes me think about a couple of things. One is adult children who’ve had alcoholic parents or they may not have been sexually abused but they get neglected or physically or emotionally abused. Is that a similar kind of dynamic?

It is. It falls under what we have termed, not me personally and my coauthors, but in this research area, we call betrayal trauma, which is any situation where trauma is experienced that is perpetrated by somebody that you have some dependence on. Child abuse epitomizes that because you’re absolutely dependent on but you can be dependent on your spouse, you can be dependent on your supervisor. In the military we see this often with military sexual trauma or other types of trauma. The same kind of dynamic occurs there where we see this as coping how to maintain attachment is I put the blame on me.

One other thing that comes to mind is I see so many female patients that have alcohol use disorder or have an eating disorder. They have this experience. Maybe they’ve had childhood trauma and then they get drunk or are using commonly benzos or other things that impair you. They are raped and it’s difficult. It seems like the guilt and the shame get stuck there and telling, “If I hadn’t been drunk, this wouldn’t have happened. It is my fault.”

Treating Guilt And Shame: Everybody has defined trauma as an event or some events of chronic situation that someone is in.

I’m glad that you’re asking that question because it does get more and more complicated once that trauma-related guilt is there and the trauma and that guilt is not processed, it just snowballs. It festers and snowballs and overgeneralizes. That’s one issue about what you’re talking about is anything that we don’t process and we want to avoid and this is the cycle that we talk about in TrIGR, the more we’ve got it. The guilt becomes more powerful. We try to tuck it away more, it becomes more powerful and it comes out in all sort of ways that we don’t want it to. It also generalizes so now we start feeling guilty and ashamed about all sorts of things.

It causes us to look at ourselves differently. I have so many of my patients who are, “I’m not worth loving. I have to climb this huge expectation ladder in order for anyone to care about me. I’m worthless.”

That’s what happens is that folks do things to try to overcompensate for whatever they think their lack is or their defect is. They also don’t take good care of themselves because they don’t think they’re worthy of it. They also engage in a lot of avoidance because there’s so much distress that comes with guilt and shame. We talk about that in the book as being some of the most diverse types of negative feelings we can have. We want to avoid, self-medicate and lots of other ways. What that does is we know that when we avoid, we don’t just avoid one thing, avoid is also overgeneralized. If I want to avoid feeling guilty or ashamed or thinking about my trauma, I’m not going to be paying attention to any other feelings.

One of the things that feelings does for us, including guilt and shame is it gives us information about our behavior and our environment. What we might want to change or not change. I’m going to give you an example of why guilt might be good and helpful in and of itself when it’s not attached to trauma and trauma-related distress. We have guilt in the first place because it’s informative and it helps us identify what our values are. Think of the situation where I’m working so hard at work and I miss my child’s first tap dance performance because I have all these responsibilities. I feel guilty about that.

That tells me I had this value of being a present mother. Next time I’m going to rearrange my schedule or I’m going to think more about how much time I want to spend at work. It’s very useful and functional. You don’t want to be avoiding it altogether. The problem is if it’s distressing guilt that’s been festering and that’s associated with trauma, I’m going to want to avoid it, but I also then avoid the good part of the guilt, the functional part of the guilt. Then I act more and more, less and less in line with my values. I may neglect my daughter’s next performance too.

You self-medicate that guilt each time with something else, whether it’d be a substance, food or fill in the blank.

We are so good as human beings at avoiding. We’ve invented a million and a half ways.

[bctt tweet=”PTSD and post-traumatic stress are usually co-morbid with other things and most commonly is depression.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]You talk about something called NAGS.

That’s our model. That’s our cycle. The way that we conceptualize and have seen this over and over again in our clients and also in some of the research that we’re doing that support a model. It follows on the question you had, “Is there a possibility for somebody to have trauma and not experience guilt?” Yes, there is. What happens is they experience the trauma and something bad happens we have this guilty feeling like, “Did I do something that caused this?” If we think about it, process it and we allow ourselves to have all these feelings and even feel guilty, maybe momentarily, we can evaluate and go, “I really did everything I could, given the information I had, the opportunities I had, the options I had and the skills I had. There’s nothing else I could’ve done.”

That’s processing yet, and I don’t have to hold onto that anymore. Move on, next. I might even say, “I did everything I could, but I think next time I’ll know now that caused that. I will try option B instead.” It won’t produce any ongoing guilt. It’s like, “Great, now I know.” In those situations where the guilt and the shame is so aversive that we avoid it or we’re just in the habit of avoiding because maybe we’ve had prior trauma or the context of the trauma is such that we are compelled to avoid even more.

Loss of life for example, that seems like it would be harder to explain away.

It’s definitely, the more serious the outcome, the harder it is to let go of feelings, any negative feelings including guilt. Certain contexts like if you’re in combat and you just shot somebody because they’re attacking you, you don’t have time to process that. You have to keep on guard because somebody else might be attacking you or somebody was lost. When somebody’s down, you can’t sit there and mourn and evaluate what you did or could have done. You have to keep going. There are certain traumas like that or betrayal trauma where you have to pretend like it’s not happening.

You have to put it on you in order to maintain attachment, then that compels some avoidance of the reality of it. Those kinds of contexts mean that you’re more likely to avoid. There are certain things that just put you at risk for avoiding. Once you step into that avoidance realm, then there’s that whole NAGS cycle of non-adaptive guilt and shame. There’s an adaptive form of guilt and shame and there’s a non-adaptive form. That’s when you get stuck in avoiding and therefore the guilt and the shame increases. You act less and less in line with your values and then you are more likely than to feel more guilt and shame.

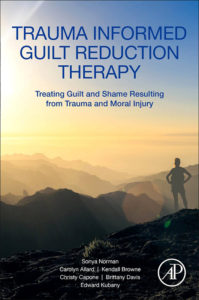

Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy: Treating Guilt and Shame Resulting from Trauma and Moral Injury

I’ve been thinking about all the reports lately about suicides among medical students. How many times even in my own career that I’ve felt guilty about a decision I’ve made. It’s something that didn’t go the way that I had hoped or somebody died. Not necessarily even because of a mistake I made, but because they died, things happen. How difficult it is to wrap your head around the amount of responsibility that you have as a physician, which I would think it’s very similar in many ways to what the military guys experienced. They’re responsible for other people and other people’s lives and nobody trains you for that. They definitely don’t train you for that in med school.

In fact, in the military, they train you to feel guilty. They tell you you’re absolutely trained to believe that if something happens, if you’re a superior that it’s your responsibility and you’re going to be held accountable for it. When we work with those folks, we have to really talk about what’s the definition of responsibility and how accurately is that term used. Just because you’re accountable for something doesn’t mean you have control over something. That’s one thing and absolutely for folks who are medical school students, who are medical providers, and we talk about this in the book as well, there’s growing research in this area in particular that we also review in the book that folks do feel initial guilt of like, “Did I do something? Is there something I did that caused this?” If you don’t process that, it can lead to NAGS cycle and we’re seeing that to be very common in medical providers.

In that case, the NAG would be, I don’t ever make mistakes. I avoid facing the likelihood that I could ever make a mistake. I’ve seen a number of providers who go down that road and that’s not a healthy way either.

It also makes sense though that I think encouraged by some of the litigious culture that we have around.

The malpractice companies are always sending us articles about how patients are less likely to sue if you admit that you’ve made a mistake.

I saw some of the research and the studies are looking at that and I was so excited to hear that. Some medical groups are adopting that because it does, and I was putting myself in that place and a patient whose something wrong happened to. I thought I would be much more ready to forgive somebody who admitted that they made it for me.

It’s a horrible mistake and didn’t intend to, etc. How do you treat to be NAGS non-adaptive mechanisms when they are in the presence of something like an eating disorder or substance use disorder? Does that change your approach at all?

One of the nice things that we’re finding about this approach is that it’s transdiagnostic. We’re no longer just focusing on PTSD. We call it like a posttraumatic stress reaction, however, that might present for you if there’s guilt and shame related to that, then we will address the guilt and shame related to that. We’re less concerned about addressing each symptom and more of the underlying. We’re seeing this might be a mechanism through which these symptoms present or develop. We don’t find that we need to change the strategies so much depending on what symptoms people present with.

[bctt tweet=”We have guilt in the first place because it’s informative and it helps us really identify what our values are.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]I don’t know if you’ve heard of Gabor Maté and the work that he’s done. He says that trauma is the root of all addictions. I would include eating disorders. I rarely see an eating disorder client or a substance use disorder client who does not have some kind of trauma. His definition of trauma is any loss of security, loss of safety, and loss of a sense of peace or an essential part of yourself. For the most part in my career, everybody has defined trauma as an event or some events or chronic situation that someone’s in. When you’re talking about getting to the root and using this trans diagnostically, I think his definition of trauma also makes sense too. For some people, there isn’t one event that they remember, and yet they have all of the trauma pathology of someone who does remember an event. Do you see that too?

One of the things that I have seen in my years of practice is that it’s not as important to me and my work with the client. If their experience, their trauma fits any definition neatly, it’s more about the impact of the experience on them. I don’t spend a lot of time figuring out does it fit the DSM criteria? Does it fit that criterion? I spend more time assessing their perception of it, the impact of it on them, and whether or not guilty and shame are part of it. That helps me decide how to target what’s going on.

I know in your book you describe a very elegant way of approaching these issues and particularly approaching guilt and shame. If someone is reading and they’ve been going through the guilt-shame spiral, what are some of the first steps that they can take to start the healing process?

One of the first steps that we encourage is addressing the avoidance and so continuing the avoidance. You already know as I will talk to my clients that you know where that leads you. You can do that all by yourself. You don’t need me to help you with that. You know exactly the outcome of that because you’ve been doing it in some cases for decades. What we propose is the opposite of that is the opposite of avoidance, which is confronting. We have systematic ways of doing that in a supportive way, on the other hand, somebody to be ruminating over something terrible happened. People are stuck with avoidance or rumination and a little bit of both.

It alternates throughout the day, sometimes, even frequently. We know that that doesn’t work either to just, “This is terrible. I did a terrible thing.” That’s not what we mean by the opposite of avoidance. What we want to help folks through is confronting what happened and thinking about what happened and their beliefs about their role about what happened in terms of do they think they helped cause this? Did they think they should have prevented it? Do they think they went and get their values, whatever thoughts they have that lead them to feel guilty or ashamed to identify those and then to see if they’re accurate and to see if there are different ways of looking at it?

It’s very much a cognitive behavioral therapy model where you’re like, let’s work with your thoughts, but allowing the feelings to come up and take their natural course and see if you’re accurate. We spend a lot of time, that’s the crux of the therapy is evaluating in a very realistic way whether what you’re telling yourself all this time is accurate and if not, what else could you be telling yourself that’s more accurate? That leads to different feelings and less avoidance. You’re reversing that cycle, as opposed to going down the spiral, you’re going back up and then you have control of your life.

I see a lot of patients struggle with is their fear of addressing it. You’re saying address it, don’t avoid it. Many people are afraid of the feelings that are going to be there, reliving the trauma and so on. How do you address that?

A lot of preparatory work that we do, the psychoeducation and providing the rationale for doing this and normalizing their reactions and their responses and letting them know that they’re not alone. We’ve got a book now and even before that we had a whole manual that we would be providing and some of the work we’d done was in groups. People got to see that this is like a phenomenon. This is a human phenomenon that I’m stuck in and I don’t have to be. There’s opportunity here. There is “a light at the end of the tunnel.” There’s a possibility for me to be feeling a different way to have a different perspective on this.

We provide them with that hope, with that possibility and support all along the way. The therapeutic relationship is important to have non-judgment. One of the biggest obstacles that our clients report to us in seeking help feeling guilt and shame is contraindicated to feeling close to somebody. Usually it compels you to withdraw. The shame means you’re going to go isolate somewhere. You’re not going to trust other people to look at you in a fair light. You’re going to assume that they’re going to judge you as harshly as you’re judging yourself. Opening the door, having these conversations, showing nonjudgmental stance, empathy and compassion for what they’re feeling and anything that they might be afraid to tell you, it’s all sort of fodder to be worked on, to be used helps prepare people and to take that leap, that first step.

It’s really difficult. I see a lot of patients with the addictions and the eating disorders have been shamed for various reasons throughout their lives. If you make the example of someone with an eating disorder who is told, “You’re too fat at the age of five.” You have to go on a diet and then being shamed about wanting to eat certain foods on a regular basis. It’s not that’s something like that big traumatic event happened. It was being made to feel like something’s wrong with you if you want to eat more of this or if you don’t want to eat that. I’ve heard stories of parents who put padlocks on kitchen cabinets. I don’t think of anything that can make you feel more ashamed than that although there are lots of examples.

There are so many ways that we make ourselves and make each other feel ashamed. I worked with many people, their source of guilt and shame is internal but also coming from the outside and often with sexual abuse survivors, they were told that it was their fault by the abuser that couldn’t help themselves or other things like that. That’s very common as well, but you get to question all of that, you get to put that all on the table.

I could talk to you all day because I love this topic, your approach to it and how organized it is. I’m going to memorize your book. How can people get a copy of the book or access this kind of approach if they’re interested?

The book is available, finally through the publisher Academic Press Elsevier, but also Amazon and any others online.

Give us the name again, that mouthful.

[bctt tweet=”Guilt and shame gives us information about our behavior and environment and what we might want to change or not.” username=”CarolynCRossMD”]Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy or TrIGR for short and the subtitle is Treating Guilt and Shame Resulting from Trauma and Moral Injury. Moral injuries, a relatively used term to describe an experience that folks might not call trauma. Trauma can be defined in different ways but it’s the experience of having done something that goes against your values.

Can you give an example? I don’t know if that would be clear to people.

It was born out of combat military psychology. It’s what we’re seeing in combat veterans who had to shoot to kill when one of their values is “I will not murder people like I value life.” That contradicts that or being involved in some kind of war atrocity. Things build up to such an extent that you find yourself being involved in or witnessing atrocities that go against your moral judgment and values. That can be traumatic in and of itself.

Thank you so much for taking the time and I look forward to having you back again sometime.

I’d be happy to.

We didn’t cover even half of the book, that’s for sure.

I would love it if you use the therapy and the manual. We can meet back, discuss it and talk what it was like for you. If you had any questions that I could address at that point, that would be great.

I’ll talk to you soon then.

Important Links:

- Carolyn Allard

- Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy – Amazon

- Gabor Maté

- Academic Press Elsevier – Trauma Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy

- https://www.Elsevier.com/books/trauma-informed-guilt-reduction-therapy/norman/978-0-12-814780-1

About Dr. Carolyn Allard

Dr. Carolyn Allard is Associate Professor and Program Director of the PhD Program at the California School of Professional Psychology (CSPP) at Alliant International University. She is also Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego and a research psychologist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, where she served as the Director of the Military Sexual Trauma & Interpersonal Trauma Clinic and the Advanced Fellowship in Women’s Health for over 10 years. Dr. Allard is a licensed psychologist in the state of California and has her Board Certification in Clinical Psychology.

Dr. Carolyn Allard is Associate Professor and Program Director of the PhD Program at the California School of Professional Psychology (CSPP) at Alliant International University. She is also Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of California San Diego and a research psychologist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, where she served as the Director of the Military Sexual Trauma & Interpersonal Trauma Clinic and the Advanced Fellowship in Women’s Health for over 10 years. Dr. Allard is a licensed psychologist in the state of California and has her Board Certification in Clinical Psychology.